Original Article

, Volume: 12( 10)Natural Resources Policy Environment in Uganda, Implication for Gendered Adaptation to Climate Changes

- *Correspondence:

- Bomuhangi A , School of Forestry, Environment and Geographical Sciences, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Makerere University, P.O. Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda, E-mail: abomuhangi@gmail.com

Received: August 04, 2016; Accepted: October 25, 2016; Published: October 27, 2016

Citation: Bomuhangi A, Namaalwa J, Nabanoga G, et al. Natural Resources Policy Environment in Uganda, Implication for Gendered Adaptation to Climate Changes. Environ Sci Ind J. 2016;12(10):117.

Abstract

This study examined how natural resources policies and action plans in Uganda may shape gendered climate change adaptation. It demonstrated that although majority of the reviewed natural resources policies and action plans fail to identify climate change as a policy issue, they propose strategies relevant to climate change adaptation. It also revealed that while gender is largely considered as an issue that is relevant to climate change adaptation, seldom do the policy documents mainstream gender within the proposed policy interventions identified to achieve the aspirations of the policies. Proposed climate change interventions seldom link to particular gender tenets and hence undermine gendered adaptation. Most of the policy interventions were found to adopt a gender-neutral approach, ignoring the differential characteristics of women and men. The study concluded that with this narrow approach to gender vulnerability, targeted climate change interventions that take into consideration these differences will likely not be developed and instead simplistic, short-term non-gender equality interventions will be designed.

Keywords

Adaptation; Gender; Climate change; Policy

Introduction

The need to adapt to climate change is now widely acknowledged [1-5]. However, identifying what, and how to adapt to changes in climate remains far from being clear [6]. Existing literature has successfully identified different factors ranging from scientific uncertainty, through to the current state of technology, the availability of financial resources and short time horizons, which most constrain effective adaptive planning [7,8]. However, there is growing appreciation amongst policy makers and society that the policy context in which adaptive decisions are made must also be considered as it may have a similarly constraining effect [6,9,10]. The perceived need to integrate a gender and climate change perspective in policy making has undoubtedly become more acute [9,11,12] because climate change has differential impacts to men and women [6,13-15].

Most of the policies addressing climate change have not been gender neutral [16]. Skutsch [17] offered two arguments for including gender considerations in the process of climate-change policy development: the idea that such gender mainstreaming may increase the efficiency of the climate-change process; and the idea that if gender considerations are not included, progress towards gender equity may be threatened. In other words, the quality of a given policy will remain unacceptably low, if the discourse does not consider the gender issues, including relevant differences between the experiences of the women and men. Gender insensitive policies tend to exacerbate existing inequalities and vulnerabilities [17-19].

It is only through gender sensitive climate change policy making and programming that the vulnerabilities of women and their unique environmental knowledge and life experiences in environmental adaptation can be addressed [9,14]. Gender needs to be integrated into all adaptation policies so as to realise equitable adaptation [9,20].

A large number of the poor in Uganda are women, who also largely depend on local natural resources for their livelihoods [21]. These women are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change [22] and might require distinct interventions other than those that target men or those that assume society to be homogeneous [22,23]. While some existing literature [24-26] has attempted to identify, and examine the national and sectoral policies geared towards better climate change adaptation, discussion of gender and its inclusions in natural resources policy documents remain just but rhetoric. There is therefore need to examine whether the existing policies consider gender at both the policy issues identification and strategies level and how the results can be used for designing and improving responses to climate change in Uganda.

The current study therefore examined whether the climate change policy environment in Uganda for adaptation is gender responsive. The study questioned whether gender and climate change are seen as policy issues or are simply hidden in some of the strategies proposed to achieve the aspirations of the national policies, and what implications this has for gendered adaptation to climate change.

Identification of gender and climate change as policy issues normally determines the scope to examine gender and climate change considerations and to develop a constructive approach to gender differences and inequalities in relation to climate change adaptation. If the issues are narrowly defined or not defined at all, then, the potential for considering the issues are reduced [27]. The extent to which gender and climate change issues are considered and integrated into existing policy fields is critical for the attainment of enhanced adaptation to climate change [6,28]. This is because the policy context in which adaptation decisions are made may have a constraining effect [9].

The specific objectives of the study were to: (i) assess how climate change is integrated in Uganda’s policy environment, (ii) unveil how gender issues are mainstreamed in Uganda’s climate change related policies and action plans and (iii) document the gender gaps in Uganda’s climate change related policies and action plans

Materials and Methods

Methods

To understand the inclusion of climate change in Uganda’s natural resources policy environment, the study reviewed 12 natural resource policies and 6 action plans in the environment and Natural resources sector. The policy documents and action plans were classified into two categories. The first group considered policies that were formulated and enacted before climate change issues become a significant policy issue in Uganda’s policy agenda. While Uganda ratified the UNFCCC in 1992, climate change issues did not become a national priority area of action until ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in 2002. Upon ratification of the Kyoto Protocol, Uganda was obligated to adopt and implement policies and measures designed to mitigate climate change, and to adapt to the impacts resulting from climate change hence climate change considered a policy issue. The second category considered the policies and action plans that were developed after the ratification of the Kyoto protocol. The apriori expectation was that the second tier of natural resource policies and action plans were here-in expected to be climate sensitive.

Having investigated the inclusion of climate change in Uganda’s natural resources policy environment, the policies and actions plans were assessed whether they mainstreamed gender (men and women’s issues) in the strategies designed to achieve the aspirations of the policies. The policy and action plans were also classified into two categories: That is policies and action plans enacted before 2007 and policies enacted after 2007. In 2007, a Gender policy was enacted and as a result, gender considerations became a significant policy issue in Uganda policy agenda. The apriori expectation was that policies and action plans developed and enacted after 2007 were gender transformative.

To further understand how gender and climate change issues are mainstreamed in Uganda’s natural resource policy environment, interviews were held with 15 key informants purposively selected from mainstream departments in environment sector. These included: The Climate Change Department, Ministry of water and Environment and the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, School of Gender and women studies at Makerere University and the Uganda National Meteorology Authority. Data was collected on their perception of inclusiveness of gender and climate change issues in natural resources policies.

Data analysis

Data analysis of the policies and action plans followed a 2-step procedure. To begin with, the natural resources policies and action plans were studied using deductive content analysis. Policy issues and the proposed policy strategies that relate to climate change adaptation were identified. Later Rodenburg’s set of qualitative criteria grid for screening policy instruments [16] was applied to appraise where, and how effectively the response to climate change adaptation in Uganda’s policies have integrated gender considerations. Rodenburg’s criteria grid examines whether a policy; (i) identifies gender among the policy objectives, (ii) assesses the effects of climate change on gendered relations; (iii) whether women and men’s vulnerability to the effects of climate change are considered, and (iv) whether the policy emphasizes gender responsive adaptation. These tenets of gender are particularly important in examining policies for gender inclusiveness [27].

Following the deductive content analysis of policies and action plan, theoretic thematic analysis was undertaken to identify, analyse, and report patterns within qualitative data that was generated from the key informant interviews. A range of advanced coding queries were used to analyse nuanced gendered perceptions of inclusiveness of gender and climate change issues. The results from this analysis were used to further interpret and qualify the outputs of the content analysis of the policies and action plans.

Results

Integration of climate change issues in Uganda’s environment and natural resources policies

Period before 2002: Deductive content analysis of the policies and action plans revealed that the consideration of climate change issues within Uganda’s environment and natural resources policy environment was loosely defined. This was perhaps with the qualified exception of the broad principles and strategies set out in the National Environment Management (NEM) Policy promulgated in 1994 and the National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) published in 1995. From 1996 to 2002, no precise articulation of climate change issues was found in any of the policies and action plans developed then. The most important of such policies and action plans that related to climate change were The Energy Policy for Uganda, 2002; The Uganda Forestry Policy, 2001 and The Poverty Eradication Action Plan (1997-2002). These policies and action plans made intrinsic linkages between poverty and the environment. Further still they, highlighted the need to strengthen data collection capacity to ensure adequacy and timeliness of data, assessment of user needs, strengthening human capacity and establishment of appropriate institutions to take advantage of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture (PMA) implemented between 2001-2009 made a link particularly with regard to water for production and the need to develop a robust early warning system as a major input into the process of agricultural modernization.

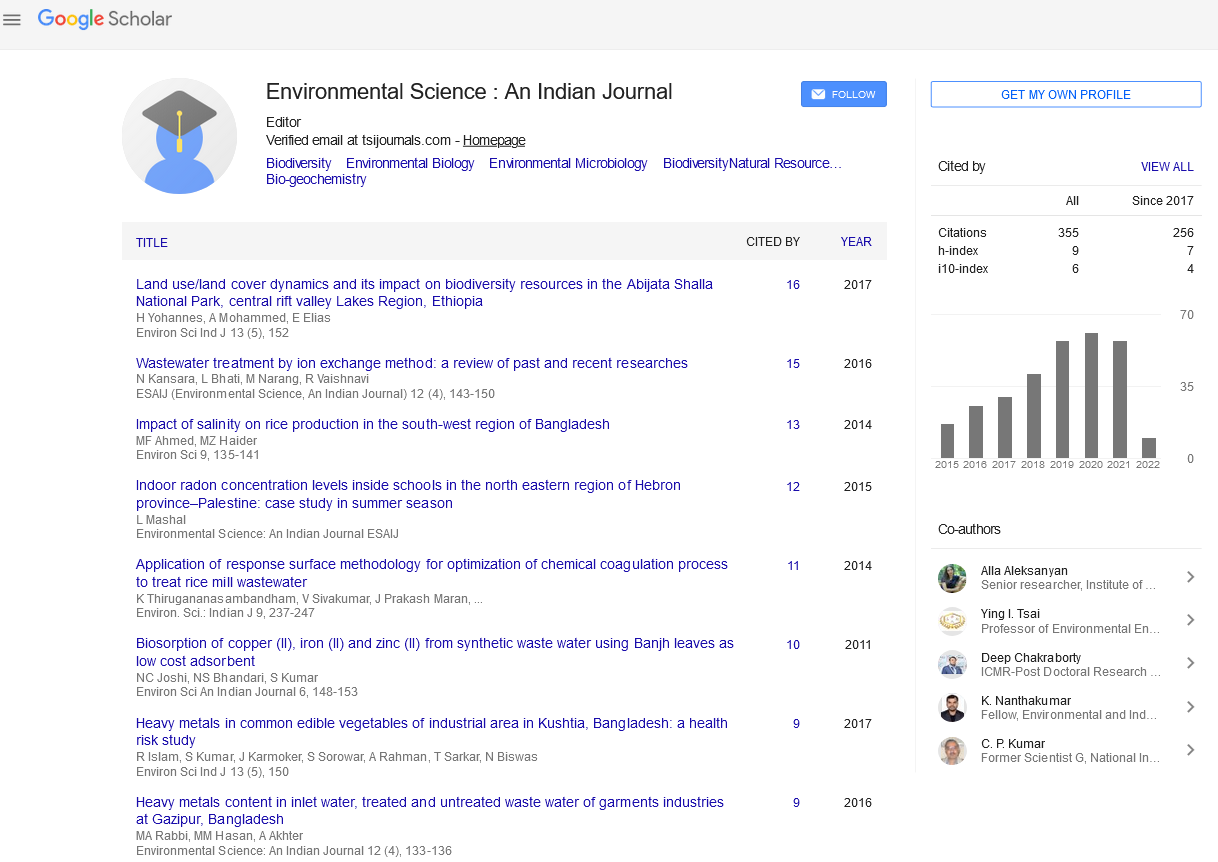

However, other than the National Environment Management Policy which identifies climate change as a policy issue/objective, the Energy policy for Uganda, 2002; the National Forestry policy, 2001; Poverty Eradication Action Plan (1997-2002) and Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture, 2001-2009 do not identify climate change as a policy issue. These policies and action plans also fail to identify practices/interventions that explicitly address climate change issues. It is however, observed that these policies and action plans make passing reference to the potential impacts of climate change on the economy and the need to take appropriate adaptation action (Table 1).

| Year | Natural resource policy | Aspect identified | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change as a policy objective | Interventions to address climate change | Interventions informing adaptation activities | ||

| 1990-2002 | 1992--- Uganda ratifies the UNFCCC | |||

| National Environment Management Policy, 1995 | + | + | + | |

| Poverty Eradication Action Plan of Uganda, 1997 | - | - | + | |

| Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture: Eradicating poverty in Uganda, 2000-2009 | - | - | + | |

| The Uganda Forestry Policy, 2001 | - | - | + | |

| The Energy policy for Uganda, 2002 | - | - | + | |

| 2002--- Uganda ratifies the Kyoto protocol | ||||

| 2003-2015 | The Uganda Gender Policy, 2007 | - | - | - |

| A National Water Policy, 2007 | + | + | - | |

| The National Land Use Policy, 2007 | + | + | - | |

| The Renewable Energy Policy for Uganda, 2007 | - | - | + | |

| National Adaptation Programs of Action, 2007 | + | + | - | |

| The National Policy for Disaster Preparedness and Management, 2010 | + | + | + | |

| National Development Plan, 2010/11-2014/15 | + | + | + | |

| Agricultural Sector Development Strategy and Investment Plan, 2010/11-2014/15 | + | + | + | |

| National Agriculture Policy, 2013 | - | - | + | |

| The Uganda National Land Policy, 2013 | + | + | - | |

| The National Environment Management Policy for Uganda, 2014 | + | + | + | |

| Climate change policy for Uganda, 2015 | + | + | - | |

| National Development Plan, 2015/16-2019/20 | + | + | + | |

+ Consideration of aspect investigated - No consideration of aspect investigated

Table 1: Consideration of climate change issues in Uganda’s natural resources policy environment.

The first statements of climate change issues were articulated in the NEM Policy, 1994. This policy laid the foundation for reforms and specific actions related to the governance of the environment in Uganda. Based on the state of knowledge at the time, the policy mainly looked at climate as a natural resource that needed to be harnessed for development. Both the guiding principles as well as the strategies outlined in the policy put emphasis on the collection, utilization and exchange of climate and atmospheric information. The policy also made muted references to the importance of climate to agriculture, as well as the need to create awareness among policy makers. However, the policy made no specific reference to adaptation interventions as a strategy for managing the impacts of climate change. The NEAP contained a package of strategies to achieve the NEM policy objectives. However, it can be argued that the focus on weather-related actions highlights the incomplete understanding of the overall impacts of climate change, which were still evolving at the time. Indeed, the NEAP emphasized the need to improve coordination of meteorological information, decentralization of the monitoring and information dissemination functions of the meteorology department, and capacity development in this area. The plan to enact appropriate legislation for the management of the country’s atmospheric environment, particularly with respect to climate and air pollution monitoring, did not materialize.

Period from 2003 to 2015: The policies and action plans developed in the period 2003-2006 did not address climate change issues. The policy regime lacked a clear articulation of the policy problem, and by implication, the regime did not contain specific policy objectives, strategies, or a definition of institutional roles to confront the climate change problem. This is evident as one of the resources persons reported that;

‘‘The mainstreaming of climate change in Uganda’s natural resources policies has been low except with the relatively new policies. This is because the integration of climate change in national policies required creation of new institutional structures such as the climate change department. Without such institutions, roles were not clearly described due of lack of a general policy on climate change: this left room for uncertainty on how the various policies interact within the line ministries and questions of who takes lead on what not addressed with reference to climate change adaptation’’ (Male, 32 years; Climate Change Department)

Policies and action plans that address climate change issues have continued to be formulated. These included: (i) the National Development Plan 2010-2014 (NDPI), the Agricultural Sector Development Plan 2010-2015 (DSIP); the Uganda Land policy, 2013; the National Environmental Management Policy, 2014, the National Policy on Climate Change, 2015 and the National Development Plan 2015-2019 (NDP II).

These policy documents identify climate change as a policy issue that needs to be addressed and they therefore map out strategies for climate change mitigation and adaptation in Uganda. Discussions with one of the resource persons in the Uganda National Meteorology Authority revealed that:

‘‘The NDP1 identifies climate change as one of those key issues that need to be addressed if economic development is to be achieved. With this in mind, all the sectors developing or revising their line policies are now tasked to identify climate change as a key policy issue. The reflection is that most of the new policies formulated during the implementation of the NDP1 are all climate proofed. They identify climate change as a policy issue, lay strategies for mitigating it as well as identify appropriate adaptation interventions’’ (Male, 46 years; Uganda National Meteorology Authority)

Uganda’s five-year National Development Plan (NDP I) 2010-2014 recognized that addressing the challenges of climate change is crucial to enhancing sustainable economic and social development. It identifies climate adaptation pathways that seek to enhance the resilience of communities prone to the effects of climate change.

In response to the national and international planning frameworks such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the post Rio +20 outcomes, the Uganda vision 2040 and the NDP1 Uganda started implementing the DSIP. The DSIP recognises the importance of addressing climate change and develops a holistic and integrated approach to planning that considers the impacts on agriculture. The DSIP particularly seeks to identify the impacts of climate change through improved forecasts and draws measures for enhancing the resilience of the affected communities. The formulation and implementation of the DSIP was followed by the enactment of the National Agricultural policy, 2012. Unlike the DSIP the National agriculture policy did does not consider climate change as a policy issue though it identifies strategies relevant to climate change adaptation.

In light of the recognition in the NDP 1, Uganda enacted the Climate change policy, 2012 as a response to reduce vulnerability to climate change, and as the most appropriate way to adjust and cope with the projected impacts of climate change in the country. The policy response to adaptation aims at helping the country address the challenges brought about by extreme weather events such increased warming, droughts, unpredictable rainfall patters, floods, and storms, thereby increasing resilience of the population, economy, and sectors. It also explores the opportunities that come with changes in climate such as; reaping rewards in some regions that might benefit from small amounts of warming favouring agriculture and livestock production.

In 2014, Uganda developed the Environmental Management Policy of 2014. This policy, unlike the NEM Policy of 1994, identifies climate change as a policy issue and seeks to ensure that all stakeholders harmoniously address climate change impacts and their causes through appropriate adaptation and mitigation measures.

Descriptive statistics reveal that 78% (representing 10 of the 13) of the policy documents and action plans enacted after 2002 identify climate change as a policy issue/objective, and further identify practices/ interventions that explicitly address climate change concerns in Uganda. The remaining 3 documents do not identify climate change as a policy issue and neither do they identify practices/ interventions that explicitly address climate change concerns. Of these three documents, two of them (National Agricultural Policy and the Renewable Energy Policy) have practices/ interventions that were not framed to explicitly address climate change but have an impact on informing assessment of vulnerability and implementation of adaptation activities (Table1). It was however surprising that the agricultural policy which is at the helm of improving the livelihoods of the Ugandan communities does not identify climate change as a policy issue that needs to be addressed. The implication for this is that the agricultural interventions promoted to achieve the aspirations of the policy may not enhance the resilience of the local communities whose livelihood is highly impacted by climate change.

In general, 61% (11 out of 18) of all the reviewed environment and natural resources policy documents and action plans developed between 1900 and 2015 both identify climate change as policy issue and propose strategies relevant to climate change adaptation. The policies and action plans were assessed based on whether (i) climate change is identified as a policy objective, (ii) interventions that address climate change are identified, and (iii) interventions that are not explicitly framed for climate change but have an impact on informing adaptation activities (Table1).

Gender sensitiveness in Uganda’s environment and natural resources policies. Uganda committed itself to address gender inequalities and take gender into account in national development by ratifying international treaties. Such treaties include; Ratification of the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights, the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. These global instruments and commitments have been domesticated through the Constitution, which adopts an affirmative action approach to achieve gender parity. Other international treaties that have been ratified and domesticated by Uganda include; the Beijing +5, the African Charter on the Rights of Women, and a pledge to implement Millennium Development Goals.

In light with these commitments, Uganda enacted a gender policy in 2007 to provide a legitimate reference point for addressing gender inequalities at all levels of government and by all stakeholders. The policy aimed to increase awareness on gender as a development concern among policy makers and implementers at all levels of government; influencing national, sectorial, and local government programs to address gender issues; strengthened partnerships for the advancement of gender equality and women's empowerment and increased impetus in gender activism.

However, before the enactment of the Uganda Gender Policy in 2007, gender issues in Uganda were already receiving some attention. Forty percent of the reviewed natural resources policy documents and actions plans identified gender as a policy issue (Table 2). Examining the gender inclusiveness of the policies and action plans involved understanding whether the policy or action (i) Identifies gender as a policy issues/ objective relevant to climate change (ii) Interventions address gender and climate change (iii) Identifies relevant gender practices not specific to climate change that may impact adaptation activities (iv) Address women and men’s vulnerability to climate change and (v) Address effect of climate change on gender relations.

| Year | Natural resource policy | Aspect identified | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender as a policy issue | Interventions addressing gender and climate change | Relevant gender Interventions informing adaptation activities | Addresses women and men’s vulnerability to climate change | Addresses effect of climate change on gender relations | ||

| 1990-2006 | National Environment Management Policy, 1995 | + | - | + | + | - |

| Poverty Eradication Action Plan of Uganda, 1997 | - | - | + | + | + | |

| Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture: Eradicating poverty in Uganda, 2000-2009 | + | - | + | + | - | |

| The Uganda Forestry Policy, 2001 | - | + | + | + | ||

| The Energy policy for Uganda, 2002 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| The Uganda Gender Policy, 2007 | - | - | + | - | - | |

| 2008-2015 | A National Water Policy, 2007 | + | - | + | - | - |

| The National Land Use Policy, 2007 | + | - | + | - | - | |

| The Renewable Energy Policy for Uganda, 2007 | + | - | + | - | - | |

| National Adaptation Programs of Action, 2007 | + | + | + | - | - | |

| The National Policy for Disaster Preparedness and Management, 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | |

| National Development Plan, 2010/11-2014/15 | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Agricultural sector development plan 2010 | - | - | + | - | - | |

| National Agriculture Policy, 2013 | - | + | + | - | - | |

| The Uganda National Land Policy, 2013 | + | - | - | + | + | |

| The National Environment Management Policy for Uganda, 2014 | + | _ | + | + | + | |

| Climate change policy for Uganda, 2015 | + | + | - | + | + | |

| National Development Plan 2015/16-2011920 | + | + | + | + | + | |

+ Consideration of aspect investigated - No consideration of aspect investigated

Table 2: Consideration of gender in Uganda?s natural resources policies.

The inclusion of gender in Uganda’s policy environment before 2007 could have been guided by the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda which recognizes equality between women and men. Specifically, it provides for gender balance and fair representation of marginalized groups; recognizes the role of women in society; accords equal citizenship rights, freedom from discrimination, affirmative action in favour of women; and articulates specific rights of women including outlawing customs, traditions and practices that undermine the welfare, dignity, and interests of women. All the reviewed policies and action plans before 2007 do not identify policy and practice interventions that explicitly address gender and climate change. They however provide relevant gender practices not specific to climate change that may impact adaptation activities with the exception of the energy policy through which gender and climate change activities could be addressed.

After 2007, with the broad exception of the Agricultural sector development plan, 2010; the Agriculture policy, 2012 and the gender policy, 2007, the remaining 13 natural resources policies and action plan identify gender as a policy issue/ objective during the preparing of the documents. Of those that identify gender as a policy issue/objective, only a substantial proportion (46%), further identify policy and practice interventions that explicitly address gender and climate change. Surprising to note is that while the Agriculture policy and the Agricultural sector development plan do not identify gender as a policy issue relevant to climate change adaptation, the agricultural policy unlike the Agricultural sector development plan, identifies relevant practice interventions that explicitly address gender and climate change. However, despite the fact that the policy identifies such interventions, it is observed that the potential for considering the gender issues in the identified adaptation intervention is reduced as the scope of adaptation is limited. Consideration of gender issues in the agricultural policy could be attributed to the fact that the policy identifies gender as cross cutting issue that may affect the achievement of the aspiration of the policy if not addressed. The Gender policy only recognizes the impact of climate change on gender but fails to effectively mainstream climate change into its proposed gender interventions.

Investigations to ascertain the gender inclusiveness of the reviewed policies and action plans revealed that 50% of these documents do not address women and men’s vulnerability to climate change effects (Table 2). Discussions with one of the resource persons from the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development revealed that;

‘‘With the adoption of the 2007 gender policy, gender is considered a fundamental issue when drafting new policies, the challenge however is that when it comes to climate change and considering its differentiated impacts, I would say that gender issues have not been adequately addressed. Most of the policy documents apart from mentioning gender as a broad construct, fail to tease out the specific gender tenets which will have an impact on adaptation’’ (Female 34 years; Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development)

Similarly, a resource person from Makerere University’s school of Gender and women studies noted that:

‘‘The integration of gender in most policies in Uganda is not adequate, the understanding of gender is not clear. Most people think that gender is about men and women and forget that there could be differences even within a group of men. If we are to consider this classification in relation to climate change adaptation, I would comfortably say that the integration of gender in policy formulation and design is not adequate. The differential power relations, roles and vulnerability aspects have not been addressed by these policies. Infact I would say that most of the climate change related policies are gender blind. (Female 53 years; School of Gender and Women Studies, Makerere University)

Amongst the policy documents and action plans that address vulnerability (n=9), the majority (78 %) neither provide any targets for women’s involvement or capacity building, nor do they contain any gender specific projects/strategies (Table 2). For example, while the Uganda NAPA project profiles generally target vulnerable groups and recognize that climate change impacts affect men and women differentially, there is no single project or target based on gender differentiation. In line with this understanding, the lack of provision of projects/strategies based on gender differentiation undermines the aspirations of these policies and action plans in achieving gendered adaptation. In-depth discussions with a resource person at the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development revealed that;

‘‘While effort has been made to integrate gender issues in some of the policies in Uganda, most of the proposed policy strategies have not spelt out any specific gender targets. Without gender targets set, the success of the policy strategies cannot be effectively evaluated. It is not just about having the word gender or male and female in the policy strategies, it is way beyond this to the inclusion of particular gender targets that can be used as indicators for measuring of gender inclusiveness (Male key informant 48 years; Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development)

The results also revealed that 22% of the polices and action plans that address gendered vulnerability these to climate do not address gender relations and power dynamics that exist at different levels (i.e. intra-household, community, sub-county, and district) and the structural constraints that underpin women’s vulnerability to climate change. Without understanding these power relations, policies, action plans and interventions that seek to enhance the resilience of the affected communities many not achieve their aspirations.

Policy gaps and recommendations to gendered climate change adaptation

Having established that the policy frameworks to mainstream gender in Uganda’s policy environment exist, the following gaps were identified:

The natural resources policies and action plans that were reviewed are largely gender blind; and for those that have attempted to address gender, they usually do so to an inadequate extent.

There is also lack of a clear link between the effects of climate change and the different vulnerable gender groups such as women/girls, the elderly, orphans and the disabled. By perceiving the different categories (women and men, young and old) as a homogenous group in respect to the negative effects of a changing climate, the climate change related policies and action plans of Uganda neglect and radically simplify the broad spectrum of women and men that exist in society. Coupled with this is the lack of evidence of the use of gender disaggregated data and gender sensitive indicators in policy formulation. One of the resources persons confirmed that;

‘‘There is lack of disaggregated statistical and qualitative data with respect to gender. There are still very few studies done to understand the differentiated impacts of climate change on women and men. Without understanding this, it’s impossible to design appropriate policy alternative or projects’ (Female key informant 53 years; School of Gender and Women Studies, Makerere University)

Despite the fact that Uganda’s policies and action plans recognize climate change and gender as cross cutting issues, each policy seems to work independently of the other with minimal interaction foreseen in the proposed strategies to achieve policy aspirations even within line ministries. The shared responsibility on gender mainstreaming seems to be no one´s responsibility. There are no clear structures of enforcement or monitoring mechanisms established to support the mainstreaming activities in the different government agencies. Discussions with one of the resource persons at the climate change unit revealed that;

‘‘Lack of a climate change mainstreaming guideline has crippled climate adaptation in Uganda. Without a mainstreaming document to coordinate the sector, efforts to mainstream climate adaptation may not be successful across all ministries. It is even complex when gender issues are to be incorporated. What we see is lip service by the line ministries which cannot be implemented without the right policy instruments. There is lack of coordination among the ministries (Male key informant, Male 32 years, Climate Change Department)

Some of the reviewed policies and action plans also lack a clear dissemination and implementation strategy, an indication that the majority of policies and action plans remain on paper and have not been fully implemented. Partly this can be attributed to the inadequate budget allocations to implement and achieve the aspirations of the policies. There is no indication of resource allocation for gender specific interventions which are attributed to the fact that majority of the policies do not identify gender as a policy issues that needs to be addressed but rather as a cross cutting issues thus narrowing the scope of the interventions developed.

In light of the above policy gaps, five policy recommendations were drawn from the interactions with the key informants, first that the Ugandan government should undertake systematic gender analysis of all natural resources related policies right from issues identification to the proposed adaptation interventions in order to identify the gaps that need to be addressed, Secondly, policy measures and strategies specifically to address gender and climate change adaptation at both national and regional levels should be developed, Third, the capacity of relevant stakeholders at national and local levels should be strengthened to promote gender-sensitive approaches to climate change adaptation. Fourth, there is a need to promote gender sensitive research and training in climate change and review individual policies and legislations to take into account a gender perspective. Lastly, there is a need to enhance the capacity of the national coordinating institution to mainstream gender into national climate change policies and operations through the development of gender sensitive policies and action plans.

Discussion

The study revealed that while majority of the reviewed environment and natural resource policies and action plans identify climate change in the proposed interventions to achieve the aspirations of the policies, majority of these policies and action plans do not identify climate change as a policy issue. The implication for this is that the Ugandan government is unprepared for the possible risks arising from change in climate as the potential for climate change adaptation is reduced through narrow or deficit definition of the policy issue. Adaptation to climate change requires that climate change issues are mainstreamed from the policy issues identification phase; this is because the context in which adaptive strategies and decisions are made stems from the way the policy issues are framed. Niang-diop and Bosh [28] argue that while the process of formulating policy options is an important step in the integration of adaptation measures in public policy, when the policy context is not defined, then the potential for adaptation is reduced.

In this regard, Uganda’s environment and natural resources policy environment could largely be described as nascent and insufficient since consideration and priority afforded to climate change adaptation in the key line policies is and has remained apparently low. This could be due to the fact that some of existing policies in Uganda were designed and implemented long before climate change was a significant national priority of action, therefore, climate change issues were not placed on the government’s policy agenda although Uganda had earlier ratified the UNFCC in 1992. In few of the policies and action plans where climate change issues have been considered, implementation of the proposed interventions has rarely occurred. This finding confirms what Namaalwa et al. [29] report that, despite the fact that Uganda developed the Uganda NAPAs in 2007, limited implementation of the prioritized adaptation strategies has happened.

The study reveals that Uganda’s NAPA just like other environment and natural resources policies and action plans have not been sufficiently popularized and many government and nongovernment actors are not aware of them. Biesbroek et al. [30] and Ford et al. [31] report similar findings of low climate change mainstreaming in public policy implementation of developing countries. According to Yohe et al. [32], failure to mainstream climate change in policy is attributed to weakness of state institutions that are unable to design and implement public adaptation policy and as well as lack of funding to implement the policy and strategies set forth. These finding supports findings by Namaalwa et al. [29] who reported disconnect between climate policy strategies formulation and implementation. Public policies often fail to realize their stated intentions. Implementation research has made clear that goals and objectives contained in law and policy documents often stay on paper because of the numerous obstacles that plague implementation processes [33].

The study also revealed that Uganda’s climate change adaptation policy regime has largely been shaped by the 1995 Environmental Management policy, and the NAPA that was developed in 2007. However, it should be noted that the NAPA is not an articulation of policy principles and strategies but rather a collection of agreed response actions generated through a participatory process which have never fully been implemented due to under funding from the Ugandan government and the complexity of securing funding from the Global Environment Fund [29,34]. It should also be noted that before 2007, climate change was loosely integrated into the policy environment of Uganda. This finding confirms Tumushabe et al. [34] who reported that a more comprehensive articulation of the potential impacts of climate change and the need for a fairly aggressive policy response did not take hold in Uganda until the formulation of the National Adaptation Programme of Action in 2007. Climate adaptation before 2007 was largely shaped by broad principles defined in the environmental policy of 1995 which were lacking in detail with regard to adaptation and therefore often appeared to be little more than “empty shells,” in delivering climate adaptation.

Attention given to climate change in Uganda’s natural resources policy environment after 2007 can be explained by the fact that by 2007, the knowledge level on climate change had advanced considerably among the policy makers and, to a large extent, the impacts of climate change were becoming evident. For example, in 1998, Uganda experienced the El Nino phenomenon which had devastating effects on the economy. Feeder roads were destroyed, cutting off access to markets for major rural products. The slowdown in agricultural output registered in 2000 was directly linked to the 1999 drought that hit most of the country following the 1998 El Nino phenomenon [34]. As evidence of the effects of climate change continued to emerge and become more manifest particularly in extreme weather events, the policy narrative on climate change began to evolve. The regular occurrence of droughts directly impacting on agriculture and food security, the persistent flooding in many parts of the country and the outbreak of major epidemics led to increased political and policy consciousness of the need to confront the phenomenon of climate change. Similarly, in 2002 Uganda had ratified the Kyoto protocol which provides the basis for an international response to the challenges of climate change. By signing and ratifying Kyoto Protocol, Uganda committed to adopt and implement policies and measures designed to mitigate climate change and to adapt to the impacts resulting from climate change as reflected in the policies and action plans developed there after by the Ugandan government.

While there is an existing framework for the inclusion of gender issues in the formulation of policies and action plans in Uganda. The study however revealed that between 1990 and 2007, gender issues were generally treated as cross-cutting issues, not given priority as policy issues/objectives and therefore no gendered interventions developed in the natural resources policies. Failure to identify gender as a policy issue or narrowly defining the issue reduces the potential for considering gender issues. This means the scope of the interventions developed to achieve the aspirations of the policy will be limited and that there could be possibilities of developing non-gender equality adaptation interventions. This would therefore imply that the benefits of the interventions in addressing the gendered impacts of climate change will be limited. Considering gender at an issues identification level of the policy processes contributes to a more informed view of policy options and impacts at the policy interventions level. According to the United Nations [27], gender perspectives should be included in the formulation of the policy issue/question to be addressed. The definition of the issue will determine the scope to examine gender issues and to develop a constructive approach to gender differences and inequalities. It was however observed that there was a shift in the trend of policy formulation, with most policies and action plans developed and enacted after 2007 identifying gender as a policy issue/objective relevant to climate change that needs to be addressed. This could be attributed to the fact that Uganda had enacted a gender policy in 2007 which called for gender mainstreaming along all government agencies and polices.

Despite this policy shift, the integration of gender into respective policy interventions remained low. Majority of the policies enacted even after the adoption of the gender policy failed to identify policy interventions that explicitly address gender and climate change: most policies continued to develop simplistic and short term interventions that do not promote gender equality. The dangers of gender issues being marginalized in climate change adaptation interventions are particularly acute as climate change affects men and women differentially. It is argued therefore that in order to develop gender transformative climate change adaptation interventions, there is need to not only to identify gender at a policy issues levels but rather to mainstream gender within the relevant interventions developed to achieve the aspirations of the policies, which means making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences as an integral dimension of policy and practice intervention design. If this is realized, it will ensure that women and men benefit equally from the adaptation process, thereby resulting in effective and sustainable policies. We however argue, that if adaptation policies and interventions follow a “gender-neutral” path- way, the implementation of the policy interventions will not garner the knowledge and skills, nor address the practical and specific needs of both men and women who are greatly impacted on by climate change.

The study also revealed that although most of the policy documents and action plans do not identify policy and practice interventions that explicitly address gender and climate change, majority of the policies and action plans identify relevant gender practices/interventions not specific to climate change that may impact adaptation activities. The fact that these policies contain interventions that may impact the adaptation process is a good entry point for gender and climate proofing of such policies. As this provides policy makers with the ability to explore the scope of recalibrating the policy and practice intervention particularly with respect to time scales so they synergize with climate adaptation requirements. It is therefore argued that as the country embarks on addressing the impacts of climate change, there is need to climate proof all the policies that may have an impact on climate adaptation.

The results also showed that while some effort has been made to develop climate change interventions that address men and women’s vulnerabilities, majority of the policies and action plans have not developed interventions that address gender relations that exist at different levels and the structural constraints that underpin men and women’s vulnerability. Given the gender differences and inequalities within societies, it cannot be assumed that women and men will be affected equally or that they will have equal opportunities for participation in climate adaptation. Special attention is needed to ensure that initiatives are not assumed to affect all people in the same manner, as this could unintentionally increase gender inequality. The power relations between men and women can greatly influence the perspective of men and women on climate change adaptive capacity and vulnerability. It is critical that gender sensitive climate change adaptation policies pay attention to the similarities and the differences between men and women with regards to skills, experiences, access to assets, knowledge, and viewpoints, and thus give equal value to these in terms of dealing with climate change issues. It is argued therefore that there is need to develop policies that are not only climate-specific but gender sensitive at the same time serving to enhance rural families' livelihood options and making them more resilient if their resource base changes.

Conclusion

The study unveils that gender mainstreaming in Uganda’s environment and natural resources policies is still rhetoric despite the existence of both the legal and policy frameworks to mainstream gender issues. This study also demonstrates that the majority of the reviewed environment and natural resources policies and action plans do not link climate change to particular gender tenets and hence undermine gendered adaptation. Most of the policy interventions were found to adopt a gender-neutral approach, ignoring the differential characteristics of women and men. With this narrow approach to gender vulnerability, targeted climate change interventions that take into consideration these differences will likely not be developed and instead simplistic, short-term gendered interventions will be designed.

References

- Burton I. Vulnerability and adaptive response in the context of climate and climate change. Climatic Change. 1997; 36(1):185-96.

- Bryant CR, Smit B, Brklacich M, et al. Adaptation in Canadian agriculture to climatic variability and change. Climatic change. 2000;45(1):181-201.

- Paavola J, Adger WN. Fair adaptation to climate change. Ecological Economics. 2006;56(4):594-609.

- Bryan E, Deressa T, Gbetibouo GA, et al. Adaptation to climate change in Ethiopia and South Africa: options and constraints. Environmental Science & Policy. 2009;12(4):413-26.

- Hisali E, Birungi P, Buyinza F. Adaptation to climate change in Uganda: evidence from micro level data. Global Environmental Change. 2011;21(4):1245-61.

- Urwin K, Jordan A. Does public policy support or undermine climate change adaptation? Exploring policy interplay across different scales of governance. Global environmental change. 2008;18(1):180-91.

- West CC, Gawith MJ. Measuring progress: preparing for climate change through the UK Climate Impacts Programme. UKCIP.2005.

- Lorenzoni I, Nicholson-Cole S, Whitmarsh L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change. 2007;17(3):445-59.

- Burton I, Huq S, Lim B, et al. From impacts assessment to adaptation priorities: the shaping of adaptation policy. Climate Policy. 2002;2(2-3):145-59.

- Lim B, Spanger SE, Burton I, et al. Adaptation policy frameworks for climate change: Developing strategies, policies and measures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

- Terry G. No climate justice without gender justice: an overview of the issues. Gender and Development. 2009;17(1):5-18.

- Johnsson-Latham G. Why more attention to gender and class can help combat climate change and poverty. Gender and climate change: an introduction. London: Earthscan; 2010. 212-22 p.

- International Labour Organization. Report of the Committee on Employment and Social Policy, Employment and labor market: Implications of climate change. Fourth item on the agenda, Governing Body, 303rd Session(Geneva).2008.

- Brody A, Demetriades J, Esplen E. Gender and climate change: mapping the linkages, A scoping study on knowledge and gaps. BRIDGE, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.2008.

- Dankelman I, Jansen W. Gender, environment, and climate change: understanding the linkages. Gender and climate change: an introduction. London: Earthscan; 2010. 21-54 p.

- Rodenberg B. Climate change adaptation from a gender perspective. A cross-cutting analysis of development policy instruments, DIE Research Project ?Climate Change and Development??. Bonn. 2009.

- Skutsch M. Protocols, treaties, and action: the ?climate change process ?viewed through gender spectacles. Gender and Development. 2002;10(2):30-9.

- McNutt K, Hawryluk S. Women and climate change policy: Integrating gender into the agenda. In: Alexandra Dobrowolsky. Women and public policy in Canada. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. 107-24 p.

- Mainlay J, Tan SF. Mainstreaming gender and climate change in Nepal. International Institute for Environmental Development (IIED). Climate change. Working Paper no.2.2012.

- Bennett L. Gender, caste and ethnic exclusion in Nepal: Following the policy process from analysis to action. World Bank. 2005. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/Intranetsocialdevelopment/Resources/bennett.rev.pdf (Accessed 14th December 2015).

- Abuka CA, Atingi-Ego M, Opolot J, et al. Determinants of poverty vulnerability in Uganda. SSRN Working Paper Series, no. 203. Dublin: Institute for International Integration Studies.2007.

- Bomuhangi A, Nabanoga G, Namaalwa J, et al. Gender differentiated effects of climate change in Kapchorwa and Manafwa district, eastern Uganda (Forth coming). 2016.

- Adger WN, Dessai S, Goulden M, et al. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change. 2009;93(3-4):335-54.

- Hepworth N. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation preparedness in Uganda, Heinrich Boll Foundation, Nairobi, Kenya.2010.

- Banana AY, Byakagaba P, Russell AJ, et al. A review of Uganda?s national policies relevant to climate change adaptation and mitigation: Insights from Mount Elgon. CIFOR working paper no.157. 2014.

- Ampaire EL, Happy P, Van-Asten P, et al. The role of policy in facilitating adoption of climate-smart agriculture in Uganda. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).Copenhagen, Denmark.2015.(Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org).

- United Nations. Gender mainstreaming an overview, Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, USA.2002.

- Niang-Diop I, Bosch H, Burton I, et al. Formulating an adaptation strategy. Adaptation policy frameworks for climate change: Developing strategies, policies and measures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. 183-204 p.

- Namaalwa J, Bomuhangi A, Balikowa K. Assessing the progress of implementation of the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) for Uganda. EMIL/MWE consultancy report. Kampala Uganda. 2015.

- Biesbroek GR, Swart RJ, Carter TR, et al. Europe adapts to climate change: comparing national adaptation strategies. Global Environmental Change. 2010;20(3):440-50.

- Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Paterson J. A systematic review of observed climate change adaptation in developed nations. Climatic Change. 2011;106 (2):327-36.

- Yohe G, Malone E, Brenkert A, et al. A synthetic assessment of the global distribution of vulnerability to climate change from the IPCC perspective that reflects exposure and adaptive capacity. CIESIN (Center for International Earth Science Information Network), Columbia University, Palisades.2015.

- Hupe PL. The thesis of incongruent implementation: revisiting Pressman and Wildavsky. Public Policy and Administration. 2011;26(1):63-80.

- Tumushabe G, Muhumuza T, Natamba E, et al. Uganda national climate change finance analysis. London and Kampala: Overseas Development Institute and the Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment.2013.