Original Article

, Volume: 12( 12)Effect of Biological and Chemical Phosphorus on Yield and Some Physiological Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Under Water Deficit Stress

- *Correspondence:

- Pirzad A , Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran, Tel: 09141471338, +98(044)32779558;

E-mail: a.pirzad@urmia.ac.ir

Received: October 10, 2016; Accepted: October 24, 2016; Published: November 10, 2016

Citation: Rahimi S, Pirzad A, Jalilian J, et al. Effect of Biological and Chemical Phosphorus on Yield and Some Physiological Responses of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) Under Water Deficit Stress. Biotechnol Ind J. 2016;12(12):117.

Abstract

To evaluate the physiological responses of pot marigold to water deficit under biological and chemical phosphorus sources, a factorial experiment was conducted based on randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications at Urmia University in 2014. Treatments were irrigation (at 50% and 80% Field Capacity; FC) and phosphorus (control, triple super phosphate, phosphate solubilizer bacteria and three arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi species included Glomus intraradices, G. mosseae and G. hoi). Analysis of variance showed the significant effect of irrigation on leaf chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b and total chlorophyll, also significant interaction effect of irrigation × phosphorus on carotenoid, leaf proline, total soluble sugars (TSS), flower and seed yield. Means comparison indicated the lowest concentration of leaf chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b and total chlorophyll in plants irrigated at 50% FC. The highest leaf proline (2.6 μmol/g Fresh Weight) belonged to plants fed by chemical phosphorus at 50% FC, and the lowest one (0.63 μmol/g fresh weight) was obtained from well-watered (irrigation at 80% FC) plants inoculated by G. mosseae. At all, the reduced photosynthetic pigments of chlorophyll (-a, -b and total), and increased concentration of osmolytes (proline and TSS) were achieved under water deficit stress. In mycorrhizal plants, seed yield was improved under water deficit condition. Also, the flower yield was enhanced by biofertilizers as well as chemical P. So, the results suggested replacing the chemical phosphorus with biological sources.

Keywords

Calendula officinalis; Carotenoid; Chlorophyll; Osmolytes; Water stress; Yield

Introduction

Pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L., Asteraceae) is a medicinal plant native to Southern Europe described in many pharmacopeias. The dried flower heads have been used for their anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, antitumor and cicatrizing effects [1]. Terpenoids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, isorhamnetin, carotenoids, glycosides, vitamin C and sterols are the main chemical compounds of marigold [2]. Water deficit limits crop growth, development and global productivity, due to considerable decreasing of photosynthesis and leads to lower growth rates and performance [3]. Plants have developed complicated mechanism to water deficit stress [4]. Osmotic adjustment regarded as an important physiological adaptation related with drought tolerance by maintaining water potential under osmotic stress [5]. A range of osmotically active molecules/ions including soluble sugars, sugar alcohols, proline, organic acids, calcium and potassium were accumulated in plants under water deficit [6]. Under various levels of severe water deficit the proline content, total soluble sugars and leaf nitrogen were increased in Mung Bean plants. Furthermore, the mycorrhizal plants produced a higher seed yield, leaf phosphorus, leaf nitrogen, chlorophyll index, proline, total soluble sugars content, relative water content, root length, root volume, root dry weight and root/shoot weight ratio as compared with non-mycorrhizal plants [7]. Ghorbanli et al. [8] reported the increasing in concentration of proline in tomato cultivars under water deficit condition. Seed and biological yields were improved due to higher leaf nutrients in mycorrhizal Mung Bean plants [9].

Phosphorus (P) is one of the most important macro-elements that play a key role in protection and transfer of energy in cells metabolism. Deficiency of phosphorous may be cause to decreasing in seedling establishment and root development [10]. The most part of P used as fertilizer, convert to immobile pools through with cations (Al3+, Fe3+ and Ca2+) [11,12]. Phosphate solubilizer microorganisms (PSMs) transform insoluble form of phosphate into soluble form following to acidification, chelation, exchange reactions process and gluconic acid production [13]. PSM inocula have significantly increased cotton seed yield, with a simultaneous decrease in stalk production [14]. Although, inoculation of microbial are used for the improvement of land fertility during the last century, a relatively low work was reported on P solubilizing in comparison to N-fixation [15].

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) symbiosis, important agriculturally and ecologically, can improve plants tolerance against drought stress harmfulness [16,17]. More than 90% of plants have symbiotic relationship with AMF that can improve the uptake of nutrients especially phosphorus [18]. Gholamhoseini et al. [19] reported that in sunflower mycorrhizal plants (inoculated with G. hoi and G. mosseae) the leaf relative water content was improved, which it was better in G. mosseae. The improved root conductance is associated with a longer root and an alteration in the root system induced by mycorrhiza [20]. The developments of mycorrhizal relationships were found to be the greatest when soil P levels were at 50 mg/kg. Mycorrhizal infection of roots declines above this level with little if any infection occurring above 100 ppm P even when soil is inoculated with a mycorrhiza mix [21].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of AM fungi species, G. moseae and G. hoi, on the photosynthetic pigments, osmolytes, water status and yield of pot marigold under water deficit stress comparing other sources of phosphorus (chemical and biological).

Materials and Methods

This factorial experiment was conducted based on randomized complete block design with three replications at Urmia University (latitude 37.53° N, 45.08° E, and 1320 m above sea level), Urmia, Iran in 2014. Treatments consisted of water deficit stress (Irrigation at 50% and 80% of field capacity, FC) and phosphorus sources. Phosphorus sources included chemical phosphorus (100 kg/ha triple super phosphate), biological phosphorus (phosphate solubilizer bacteria-PSB, mycorrhizal fungi species-Glomus intraradices, G. mosseae and G. hoi) and control. Here, plants inoculated with each of mycorrhizal fungi species known as AM plants. Plants were irrigated up to FC based on above mentioned treatments. Irrigation water needed (VN) was calculated according to Benami and Ofen [22].

VN = [(FC - WP) × BD × D × (1 - ASM) × A]/100

Where, VN is the irrigation water needed before irrigation (m3), FC is field capacity (%), WP is the wilting point (%), BD is bulk density (g/cm3), D is the root zone depth (m), ASM is the available soil moisture before irrigation (a fraction), and A is the area of the field (m2).

The result of the soil analysis is shown in Table 1. In each plot (6 lines of 2 m long) seeds were sown 30 mm below the soil surface, row to row and plant to plant spacing was 30 cm and 6 cm, respectively (Supporting 55 plants/m2).

| Soil texture | Clay % | Silt % | Sand % | K (mg/kg) | P (mg/kg) | OC % | TNV % | EC (dS/m) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loam | 24 | 32 | 44 | 166 | 37.6 | 0.78 | 10.3 | 0.915 | 8.51 |

Table 1: Soil physicochemical properties at 0 cm to 30 cm of experimental site.

Measurements

Leaf chlorophyll (chlorophyll-a, b and total chlorophyll) and carotenoid content were measured according to Gross [23] method improved by Lichtenthaler [24] in 0.25 g of fresh leaves (40 Days after sowing, from 10 leaves of the main branch). Fresh material samples were extracted with acetone (80% v/v) in sealed tubes kept at room temperature in dark. Upper zone of centrifuged extraction (centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes) was taken for reading by spectrophotometer at 470, 646.8 and 663.2 nm wave lengths. Photosynthetic pigments concentration was calculated by using the following equations [24]:

Chlorophyll a (μg/ml) = (12.25 × OD663.2) - (2.79 × OD646.8)

Chlorophyll b (μg/ml) = (21.50 × OD646.8) - (5.10 × OD663.2)

Total chlorophyll (μg/ml) = (0.0202×OD 663.2) + (0.00802×OD 646.8)

Carotenoid (μg/ml) = {1000 × OD470) -1.82 Chlorophyll a- 85.02 Chlorophyll b}/198

OD 470 is shown the absorption at 470 nm, OD 646.8 at 646.8 nm and OD 663.2 at 663.2 nm wave lengths.

For proline and total soluble sugars, 0.5 g of freshly harvested leaves was grinded in 5 ml of 95% (v/v) ethanol. The insoluble fraction of the extract was washed twice with 5 ml of 70% ethanol. All soluble fractions were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were collected and stored at 4°C for proline and TSS determination [25]. Proline measured by spectrophotometer at 515 nm wave length [26] and total soluble carbohydrate at 625 nm wave length [25].

In order to measure leaf relative water content (LRWC) five upper complete and fully expanded leaves on the main shoot from five plants per each plot were picked up. After recording fresh weight of leaves, they were soaked in distilled water for four hours at 25°C. The leaves surface cleaning-off and the turgid weight was measured. Then samples dried in oven at 70°C to constant weight. Leaf relative water content was determined by using the following equation [27]:

LRWC (%)=[(FW-DW)/(TW-DW)]×100

Where FW: fresh weight; DW: dry weight, TW: turgid weight

Flower and seeds were harvested in mature stage from 1 m2 of each plot. Harvested samples dried in oven 72°C for 48 h.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) on data was performed using the general linear model (GLM) procedure in the SAS software. The Duncan's Multiple Range Test was applied to compare treatment means using the MSTAT-C software package.

Results and Discussion

Analysis of variance showed the significant effect of irrigation on the chlorophyll-a, total chlorophyll (P ≤ 0.05) and chlorophyll-b (P ≤ 0.01), and significant effect of phosphorus on chlorophyll-b (P ≤ 0.05). However, there was significant interaction effect of irrigation × phosphorus on the leaf carotenoid, proline, total soluble sugars, and the yield of flower and seed (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 2).

| Source of variation | df | Chlorophyll-a | Total chlorophyll | Chlorophyll-b | Carotenoid | Proline | Soluble sugars | RWC | Flower yield | Seed yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block | 2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.2 | 5544.19 | 2.9 | 5296.01 | 126774.62 |

| Irrigation | 1 | 0.03* | 0.12** | 0.01** | 0.014** | 3.75** | 357604** | 138.7ns | 746907.73** | 1144646.53** |

| Phosphorus | 5 | 0.007ns | 0.02 ns | 0.009* | 0.003 ns | 0.17 ns | 6158.77 ns | 29.9ns | 156433.98** | 1311308.61** |

| Irrigation × phosphorus | 5 | 0.01 ns | 0.02 ns | 0.007ns | 0.007** | 1.2** | 42928.13** | 72.7ns | 135896.21** | 690608.24** |

| Error | 22 | 0.007 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.22 | 7931.34 | 36.7 | 12723.49 | 29523.4 |

| CV (%) | - | 15.84 | 16.70 | 20.23 | 18.63 | 28.19 | 15.75 | 11.62 | 4.53 | 4.43 |

| * and ** significant at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01, respectively; df, degree of freedom; C.V., Coefficient of Variation. | ||||||||||

Table 2: Variance analysis of irrigation, biological and chemical phosphorus effects on some physiological characteristics of Calendula officinalis L.

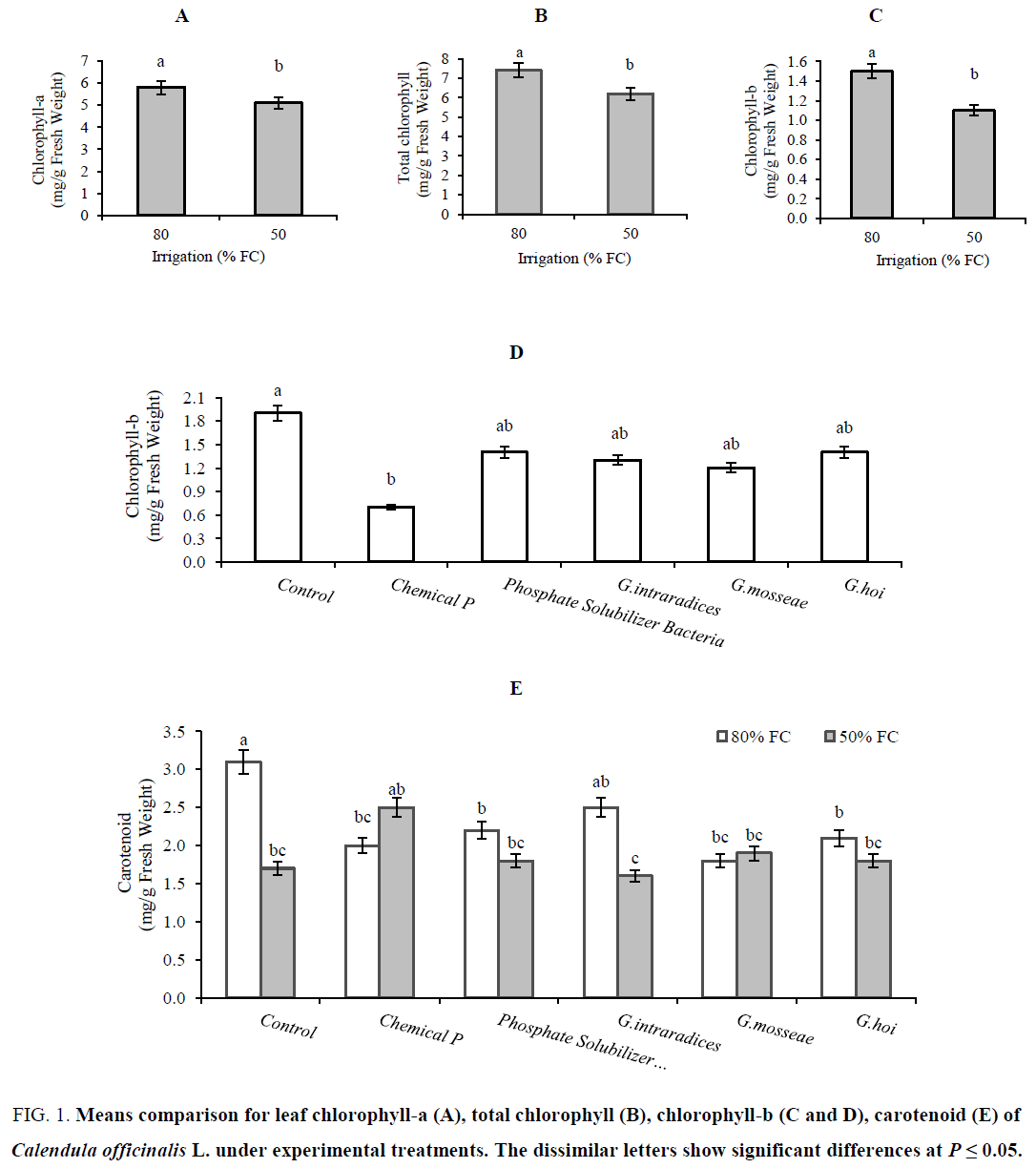

Means comparison showed that the leaf chlorophyll-a (Figure 1A), chlorophyll-b (Figure 1C) and total chlorophyll (Figure 1B) of plants grown under 80% FC (5.8, 1.5 and 7.4 mg/g Fresh Weight) was greater than 50% FC (5.0, 1.1 and 6.2 mg/g Fresh Weight). The highest content of chlorophyll-b (1.9 mg/g Fresh Weight) belonged to control plants and the lowest amount (0.7 mg/g Fresh Weight) related to chemical phosphorus application (Figure 1D). Reduction of chlorophyll-a and total chlorophyll under water deficit (irrigation at 50% FC) is due to damage the chlorophyll and prevent its production [28]. Increasing the environmental pressures could be a reason that was implicated in the oxidation on photosynthetic pigments, membranes decomposition and harm to chloroplast. Such retardation in the content of photosynthetic pigment in response to water stress was attributed to the ultra-structural deformation of plastids including the protein membranes forming the thylakoids which in turn causes untying of photosystem Π to capture photons, causing declines in electron transfer, ATP and NADPH production and eventually CO2 fixation processes [29-31]. Our results are agreement with Nyachiro et al. [32] and Paul Ajithkumar and Panneerselvam [33], they reported a significant decrease of chlorophyll-a and b by water deficit in spring wheat and Setariaitalica plants, respectively. Our results showed that the amount of chlorophyll-b in control plants as well as biological P was greater than chemical phosphorus (Figure 1D). Demir [34] indicated that the chlorophyll content of mycorrhizal pepper plants was higher than of non-mycorrhizal control plants. The highest leaf carotenoid (3.1 mg/g fresh weight) was observed in well-watered (Irrigation at 80% FC) control plants, that it was reduced in stressed condition (Irrigation at 50% FC). There was any differences between stressed and non-stressed plants in term of leaf carotenoids in all biological (AM plants and PSB inoculation) and chemical P treatments (Figure 1E).The lowest amount (1.6 mg/g Fresh Weight) related to plants treated with G. intraradices under 50% FC (Figure 1E).These results indicated the sufficient P supply for plants in biological (both AM plants and PSB treatments) as same as chemical P. Abdalla and El-Khoshiban [31] reported the progressive increase of wheat leaf carotenoids in drought stress condition.

Figure 1: Means comparison for leaf chlorophyll-a (A), total chlorophyll (B), chlorophyll-b (C and D), carotenoid (E) of Calendula officinalis L. under experimental treatments. The dissimilar letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

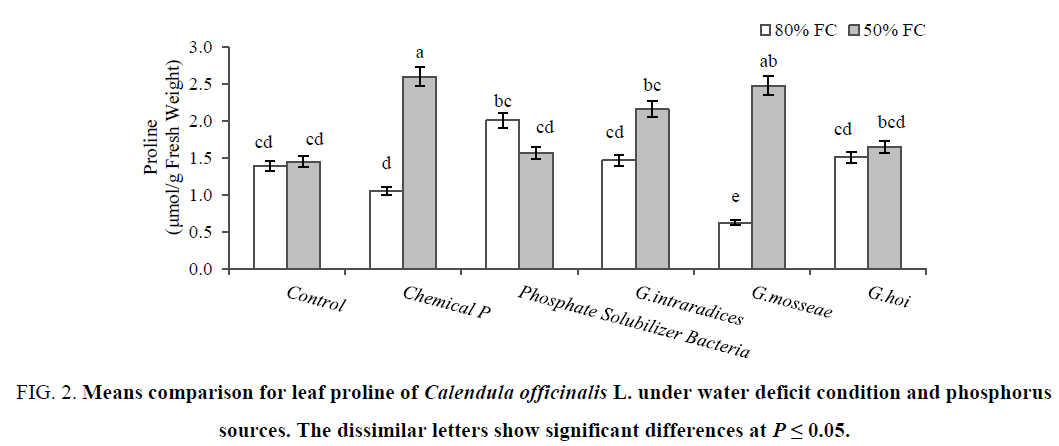

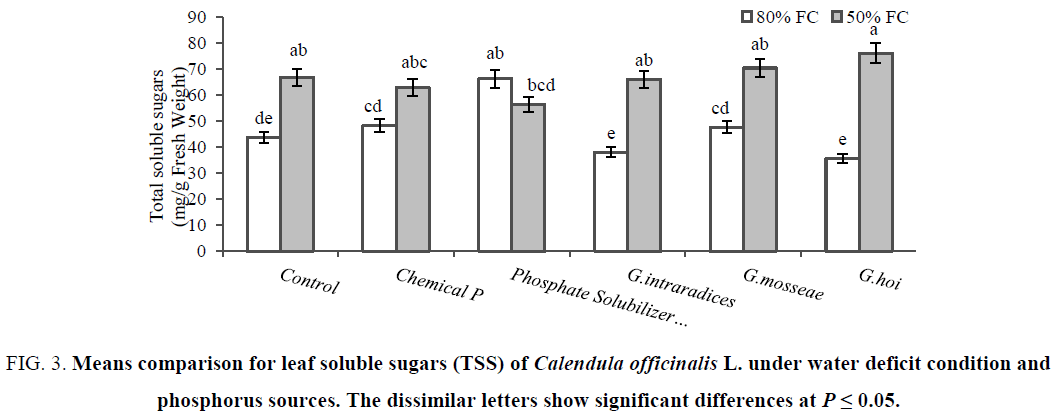

The leaf proline was the same for both two well-watered and stressed control plants. The highest leaf proline (2.6 μmol/g fresh weight) belonged to plants treated with chemical phosphorus under 50% FC as same as mycorrhized plants with G. mosseae and G. intraradices. There were no changes of leaf proline in G. hoi and PSB inoculated plants by water stress treatments (Figure 2). The greatest difference of leaf soluble sugars between stressed (76.4 mg/g fresh weight) and non-stressed (35.6 mg/g Fresh Weight) condition was observed in plants inoculated with G. hoi followed by another mycorrhizal species (Figure 3). Increasing TSS in stressed non-P treated plants exhibited that Pot marigold follow the carbohydrate accumulation as the main osmolyte. Increasing of proline under water deficit condition was reported in Cakile maritime [35] and tomato cultivars [8]. The higher proline content could be due to enhance activity of ornithine aminotransferase (OAT) and pyrroline 5-carboxylate reductase (P5CR), the enzyme involved in proline biosynthesis as well as the inhibition of proline oxidase, proline catabolizing enzymes [36]. Earlier reports mentioned that sugars protect the cells during drought by the following mechanism; the hydroxyl groups of sugars may substitute for water to maintain hydrophilic interactions in membranes and proteins during dehydration [35,37].

Figure 2: Means comparison for leaf proline of Calendula officinalis L. under water deficit condition and phosphorus sources. The dissimilar letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

Figure 3: Means comparison for leaf soluble sugars (TSS) of Calendula officinalis L. under water deficit condition and phosphorus sources. The dissimilar letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

Analysis of variance showed non-significant effects of irrigation and fertilization system on leaf relative water content (Table 2). It may be due to water providing (uptake and maintain) by mycorrhizal symbiosis and/or P supply of chemical phosphorus and PSB treatments. Shokrani et al. [38] reported that in Calendula officinalis leaf relative water content not affected by water deficit.

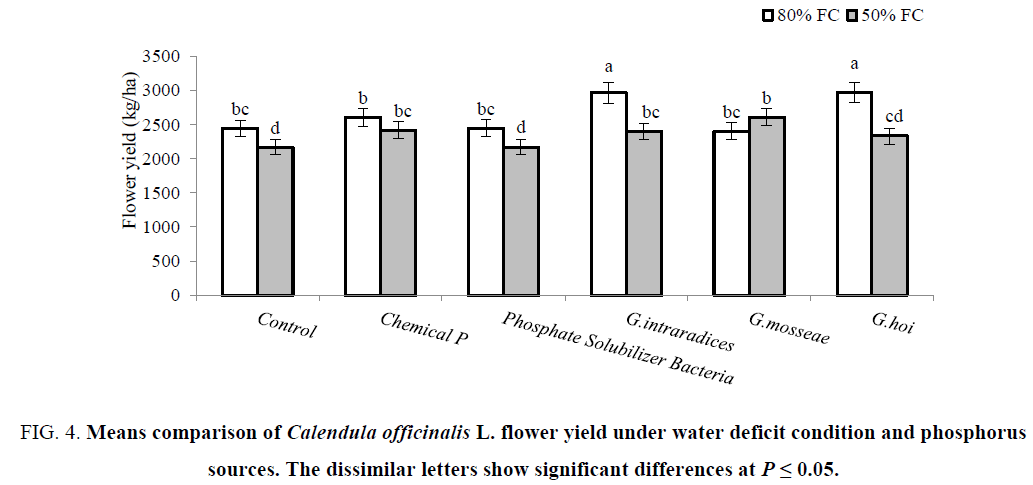

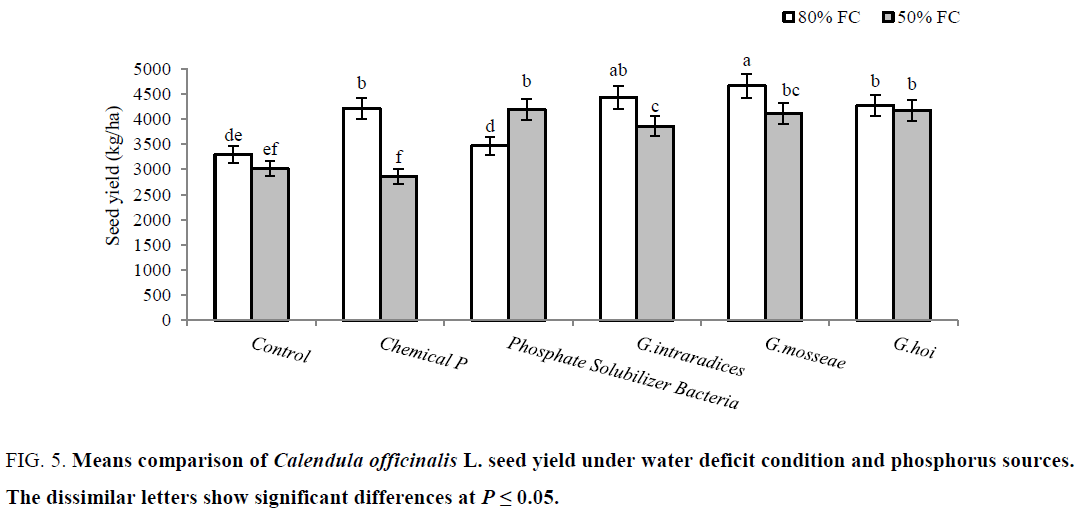

The significant reduction was observed for flower (11%) and seed (9%) yield of non-P treated control plants under irrigation at 50% FC compared to 80% FC. The yield of flower was improved by mycorrhizal plants (G. hoi and G. intraradices in non-stressed plants, and G. mosseae and G. intraradices as well as chemical P in stressed plants) (Figure 4). In non-stress condition, seed yield was improved by all three species of mycorrhiza as much as chemical P. This increase was occurred in stress condition by biofertilizer treatments (mycorrhizal plants and P solubilizer bacteria) (Figure 5). According to results, under water deficit condition flower and seed yield of C. officinalis were significantly reduced 10 and 9% respectively. Under water deficit stress stomatal closure and decrease in absorbing CO2 led to reduction in photosynthesis and plant yield [39]. Significant reduction of flower and seed yield in C. officinalis under water stress reported by Azimi et al. [40] and Shubhra et al. [41]. The yield (flower and seed) enhancements by biofertilizers are related to water absorption and mineral nutrients uptake [34]. Habibzadeh and Abedi [42] showed that both mycorrhiza species (G. mosseae and G. intraradices) significantly increased the seed yield in Mung Bean plants.

Figure 4: Means comparison of Calendula officinalis L. flower yield under water deficit condition and phosphorus sources. The dissimilar letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

Figure 5: Means comparison of Calendula officinalis L. seed yield under water deficit condition and phosphorus sources. The dissimilar letters show significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

Correlation coefficients of studied traits were shown in Table 3. These data indicated significantly positive relationships among photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, total chlorophyll and carotenoids). However, the seed yield was significantly increased by increasing flower yield. Proline was change simultaneously with TSS. There were negative and significant correlations between TSS and yield (both seed and flower) (Table 3).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Chlorophyll-a | 1 | ||||||||

| (2) Chlorophyll-b | 0.37* | 1 | |||||||

| (3) Total chlorophyll | 0.87** | 0.77** | 1 | ||||||

| (4) Carotenoid | 0.53** | 0.53** | 0.66** | 1 | |||||

| (5) Proline | -0.003ns | -0.09ns | -0.06ns | -0.007ns | 1 | ||||

| (6) TSS | -0.25ns | -0.17ns | -0.28ns | -0.34* | 0.49** | 1 | |||

| (7) RWC | -0.11ns | -0.27ns | -0.22ns | -0.33* | 0.29ns | 0.18ns | 1 | ||

| (8) Flower yield | 0.27ns | 0.19ns | 0.30ns | 0.25ns | -0.03ns | -0.55** | -0.02ns | 1 | |

| (9) Seed yield | -0.08ns | 0.02ns | -0.03ns | -0.27ns | -0.36* | -0.31* | -0.26ns | 0.38* | 1 |

| * and ** significant at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01, respectively; | |||||||||

Table 3: Correlation coefficient of studied traits.

Conclusion

The results of this study have demonstrated that water deficit stress decreased 12% chlorophyll-a, 26% chlorophyll-b, 16% leaf total chlorophyll for all P treatments, and 45% carotenoid for control non-P treated control plants. Despite the unchanged proline, leaf total soluble sugars increased about 53% in stressed non-P treated plants. This study has shown that use of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and mycorrhiza fungi could improve the plant resistance to water stress, and a reduction in use of chemical fertilizer, because of same or higher yield (Flower and Seed) due to increasing osmolytes and maintenance the RWC. A part of water deficit-induced reduction of flower and seed yield can be compensated by biological (mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate solubilizer bacteria) as same as chemical treatments. But the mycorrhizal symbiosis enhanced the yields to higher amounts than the other. Seed yield has been correlated by osmolytes (Proline and TSS) changes, but the yield of flower has been only changed negatively by TSS, that is exhibited the importance and effectiveness of TSS more than proline in Pot marigold plant.

References

- Ukiya M, Akihisa T, Yasukawa K. Anti-inflammatory, antitumor- promoting and cytotoxic activities of constituents of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) flowers. J Nat Prod. 2006;69(12):1692-96.

- Re TA, Mooney D, Antignac E, et al. Application of the threshold of toxicological concern approach for the safety evaluation of calendula flower (Calendula officinalis L.) petals and extracts used in cosmetic and personal care products. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:1246-54.

- Pei F, Li X, Liu X, et al. Assessing the impacts of droughts on net primary productivity in China. J Environ Manage. 2013;114:362-71.

- Krishnamurthy L, Zaman-Allah M, Marimuthu S, et al. Root growth in Jatropha and its implications for drought adaptation. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;39:247-52.

- Szabados L, Kovács H, Ziberstein A, et al. Plants in extreme environments: Importance of protective compounds in stress tolerance. Adv Bot Res. 2011;57:105-50.

- Farooq M, Wahid A, Kobayashi N, et al. Plant drought stress: Effects, mechanisms and management. Agron Sustainable Dev. 2009;29:185-212.

- Habibzadeh Y, Jalilian J, Zardashti A MR, et al. Some morpho-physiological characteristics of mung bean mycorrhizal plants under different irrigation regimes in field condition. J Plant Nutr. 2015;38:1754-67.

- Ghorbanli M, Gaforabad M, Amirkian T, et al. Investigation of proline, total protein, chlorophyll, ascorbate and dehydroascorbate changes under drought stress in Akria and Mobil tomato cultivars. Iranian J Plant Physiol. 2013;3(2):651-8.

- Habibzadeh Y, Pirzad A, Zardashti MR, et al. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on seed and protein yield under water-deficit stress in mung bean. Agron J. 2013;105(1):79-84.

- Khan AA, Jilani G, Akhtar MS, et al. Phosphorus solubilizing bacteria: Occurrence, mechanisms and their role in crop production. J Agri Biol Sci. 2009;1:48-58.

- Gyaneshwar PGN, Kumar L, Parekh J, et al. Role of soil microorganisms in improving P nutrition of plants. Plant and Soil. 2002;245:83-93.

- Hao XCM, Cho G, Racz J, et al. Chemical retardation of phosphate diffusion in an acid soil as affected by liming. Nutr Cycling Agroecosyst. 2002;64:213-24.

- Chung H, Park M, Madhaiyan M, et al. Isolation and characterization of phosphate solubilizing bacteria from the rhizosphere of crop plants of Korea. Soil Biol Biochem. 2005;37:1970-4.

- Ahmad F, Uddin S, Ahmad N, et al. Phosphorus-microbes interaction on growth, yield and phosphorus-use efficiency of irrigated cotton. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2012;1-11.

- Adesemoye AO, Kloepper JW. Plant-microbes interactions in enhanced fertilizer-use efficiency. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;85:1-12.

- Rodriguez RJ, Henson J, Van Volkenburgh E. et al. Stress tolerance in plants via habitat-adapted symbiosis. ISME J. 2008;2:404-16.

- Waller F, Achatz B, Baltruschat H. The entophytic fungus Piriformospora indica reprograms barley to salt-stress tolerance, disease resistance, and higher yield. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13386-91.

- Bonfante P. Plants, mycorrhizal fungi and endobacteria: A dialog among cells and genomes. Biol Bull. 2003;204:215-20.

- Gholamhoseini M, Ghalavand A, Dolatabadian A, et al. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation on growth, yield, nutrient uptake and irrigation water productivity of sunflowers grown under drought stress. Agric Water Manage. 2013;117;106-14.

- Kapoor R, Sharma D, Bhatnagar AK. Arbuscular mycorrhizae in micro propagation systems and their potential applications. Scientica Horticulturae. 2008;116:227-39.

- Schubert A, Hayman DS. Plant growth responses to vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza. XVI. effectiveness of different endophytes at different levels of soil phosphate. New Phytol. 1986;103(1):79-90.

- Benami A, Ofen A. Irrigation engineering-sprinkler, trickle and surface irrigation: Principles, design and agricultural practices. Beit Dagan, Irrigation Engineering Scientific Publications. 1984.

- Gross J. Pigment in Vegetables: Chlorophylls and Carotenoids. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York:1991.

- Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:350-82.

- Irigoyen JJ, Emerich DW, Sanchez-Diaz M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:55-60.

- Paquin R, Lechasseur V. Observations sur une methode de dosage de la proline libre dans les extraits de plantes. Can J Bot. 1979;57:1851-54.

- Turner NC. Techniques and experimental approaches for the measurement of plant water stress. Plant and Soil. 1981;58:339-66.

- Montagu KD, Woo KC. Recovery of tree photosynthetic capacity from seasonal rough in the wet-dry tropics:The role of phyllode and canopy processes in Acacia auriculiformis. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1999;26:135-45.

- MaslenkovaL T, Toncheva SR. Water stress and ABA-induced in PSII activity as measured by thermo luminescence of barley leaves. Biologie Physiologie Des Plants. 1997;50:91-4.

- Zhang M, Duan L, Tian X. Uniconazole-induced tolerance of soybean to water deficit stress in relation to changes in photosynthesis, hormones and antioxidant system. J Plant Physiol. 2006;164:709-17.

- Abdalla MM, El-Khoshiban NH. The influence of water stress on growth, relative water content, photosynthetic pigments, some metabolic and hormonal contents of two Triticiumaestivum cultivars. J Appl Sci Res. 2007;3(12):2062-74.

- Nyachiro JM, Briggs KG, Hoddinott J. Chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence and water deficit in spring wheat. Cereal Res Commun. 2001;29:135-42.

- Paul Ajithkumar I, Panneerselvam R. Osmolyte accumulation photosynthetic pigment and growth of Setaria italic (L.) P. Beauv. under drought stress. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2013;2(3):220-4.

- Demir S. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhiza on some physiological growth parameters of pepper. Turkish J Biol. 2004;28:85-90.

- Jday A, Slama I, Rouached A, et al. Growth, Na+, K+, osmolyte accumulation and lipid membrane peroxidation of two provenances of Cakilemaritima during water deficit stress and subsequent recovery. Flora. 2014;209(1):54-62.

- Debnath M. Responses of Bacopa monnieri to salinity and drought stress in vitro. J Med Plants Res. 2008;11:347-51.

- Keyvan S. The effects of drought stress on yield, relative water content, proline, soluble carbohydrates and chlorophyll of bread wheat cultivars. J Ani Plant Sci. 2010;8:1051-60.

- Shokrani F, Pirzad A, Zardoshti MR, et al. Effect of irrigation disruption and biological nitrogen on some physiological and morphological characters of leaf in Calendula officinalis L. J Med Plants Res. 2012;6(1):79-87.

- Rahmani N, Daneshian, J, Aliabadi Farahani H. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer and irrigation regimes on seed yield of calendula (Calendula officinalis L.). J Agri Biotechnol Sustainable Dev. 2009;1(1):24-8.

- Azimi J, Pirzad A, Hadi H. Effect of drought stress on morphology and essential oil of pot marigold. Int J Plant Ani Environ Sci. 2012;2(4):11-7.

- Shubhra K, Dayal J, Goswami CL, et al. Effects of water-deficit on oil of Calendula aerial parts. Biologia Plantarum. 2014;48(3):445-8.

- Habibzadeh Y, Abedi M. The effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on morphological characteristics and grain yield of Mung bean (Vigna radiate L.) plants under water deficit stress. Peak Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2014;2(1):9-14.