Original Article

, Volume: 13( 6)Comparative Study of the Physico-Chemical Quality of Water from Wells, Boreholes and Rivers Consumed in the Commune of Pelengana of the Region of Segou in Mali

- *Correspondence:

- Toure A , School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, No.26 Hexing Road, Xiangfang District, Harbin-150040, P.R. China, Tel: 00 (86) 18545130048; E-mail: touamare03@yahoo.fr

Received: October 21, 2017; Accepted: November 04, 2017; Published: November 07, 2017

Citation: Toure A, Wenbiao D, Keita Z. Comparative Study of the Physico-Chemical Quality of Water from Wells, Boreholes and Rivers Consumed in the Commune of Pelengana of the Region of Segou in Mali. Environ Sci Ind J. 2017;13(6):154

Abstract

The aim of this study is the assessment of physical and chemical characteristics of different commonly used water sources, including wells, boreholes and river in the locality of Pelengana commune, in Mali. Thirty samples of water were collected and the following physical and chemical parameters was measured: temperature; electrical conductivity; pH; nitrate; nitrite; fluoride; chloride; ammonium and Zinc. The mean values of the different measured samples were compared with the World Health Organization (WHO) Guideline Values (GVs) for drinking water quality. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the DUNCAN’s multiple comparison test for significant differences, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was also applied to all the measured parameters. The results showed that pH, ranging from 6.028 ± 0.64 to 6.58 ± 0.30 for both wells’ water and borehole waters indicate a measure of acidity. With respect to chemical parameters, zinc ions were higher than the WHO GV in all water sources as well as ammonium ions in rivers’ water. Based on the analyzed parameters, quality of these different water sources is chemically acceptable.

Keywords

Well waters; Boreholes; Rivers; Physicochemical parameter; Pelengana commune; Mali

Introduction

Water is necessary in all forms of life and plays a vital role regards to promotion of public health and the socio-economic development of human communities [1]. The most significant reserves of water sources from human point of use are the surface water and groundwater. Surface water consists of water that flows through the land in the form of streams, springs and rivers or it collects to form ponds, lakes and seas. Unlike, groundwater is situated in aquifers underground and relates to surface water across percolation, wells and sources [2].

The supply of drinking water of sufficient quality and quantity remains a crucial public health need in most African countries, including Mali, where diarrheal diseases continue to cause particularly high mortality [3]. However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 1.1 billion human beings lack good quality water and 2.4 billion do not have access to adequate sanitation. More than 2 million people, especially children below five years in developing countries with insufficient hygiene and sanitation, die each year by diarrheal diseases [4]. The water for human consumption must not contain organisms and chemical substances in concentrations sufficiently high to affect health [5].

Many studies have focused on water supply and public health in Sub-Saharan Africa, but comparatively few data are available from Mali in general and no study was conducted regarding physico-chemical quality of water consumed by people living in rural area of Segou region in particular [6].

In recent years, a rebellion associated with terrorism ruptured in northern part of Mali, bringing thousands of people to move into the peripheral areas of Pelengana commune in Segou region. These communities live in rural areas characterized by overcrowding, poor dwelling and inadequate water and sanitation. In such situations, waterborne diseases that are generally associated with poor hygiene and sanitation can assign a majority of the population [7]. Therefore, access to safe drinking water and suitable sanitation is a priority. However, most of the rural areas are not well provide with drinking water systems. Therefore, the communities living there often resort to alternative sources including wells, boreholes and rivers. The water supply for human intake is often directly sourced from groundwater without chemical, physical and biological treatment and the level of pollution has become a cause for main concern. Currently, there is no big industry in and around the study area, but household waste and municipal sewage are directly dismissed into the area. Also, water sources are susceptible for contamination due to rainfall washout, slaughterhouse activities, pesticides, excreta and various organic waste. Therefore, it could represent a dangerous source of diseases. This area has been the subject of our previous studies, given the importance of its growing population due to internal conflicts. These studies focused on bacteriological quality and heavy metal pollution of drinking water in this area [8].

This work aims to assess the physico-chemical quality of these different sources of water consumed in the commune of Pelengana. Water health state monitoring can contribute for alleviating severe water-related infections such as gastroenteritis, diarrhea, typhoid and skin diseases.

Materials and Methods

Study area

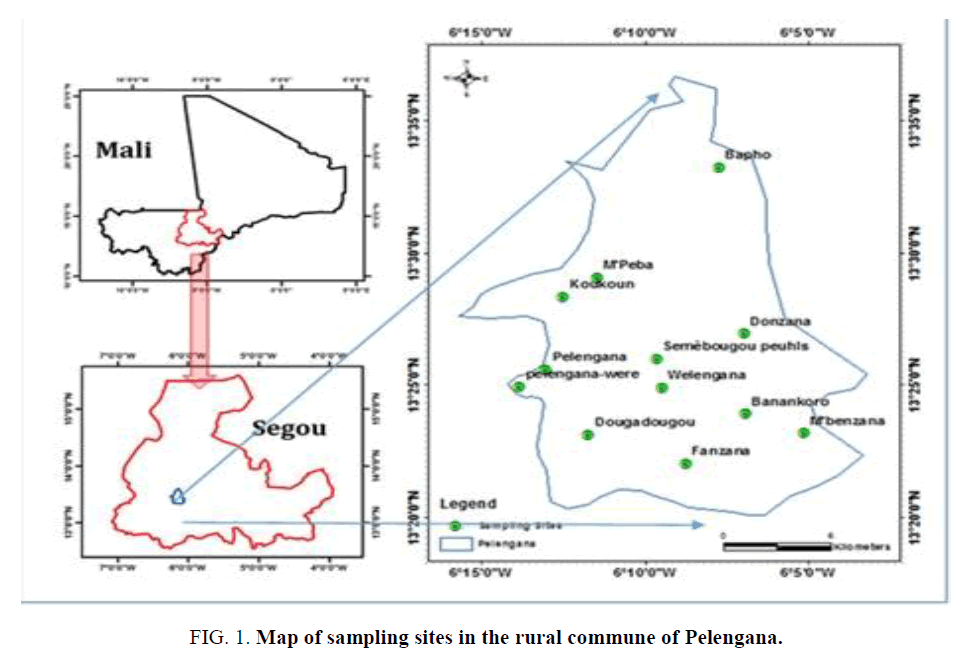

The study was conducted in the rural commune of Pelengana in Segou region (FIG. 1). The region is located in the center of Mali between 12° 30' and 15° 30' N latitude and 4° and 7° W longitude, with a total area of 62, 504 km² and a population of 2, 338, 349 based on the 2009 census [1]. The Segou region composed from 118 Communes including 3 urban communes (Segou, San and Niono) and 115 rural communes [2]. The area is irrigated through two important waterways: Niger river and Bani “one of its tributary”. Niger river flows eastwards and over 1660 km of its course in Mali and it crosses the region of Segou over 292 km. Segou region has a sudano-sahelian climate with two seasons, dry season that lasts eight months (October-May) and rainy season that lasts four months (June-September). Rainfall of the region ranges between 200 to 800 mm per year and the average temperature is 28°C [3]. Agriculture, livestock and fishing are the main activities of the region [4].

Sample collection

The sampling was carried out once each month from July 2016 to April 2017 in each water point. The sampling was effectuated according to a completely randomized device with three treatments and ten repetitions each to ensure the representativeness. A total of thirty water samples were collected for physico-chemical analyses. Treatments included wells, boreholes and river (Niger) water. Samples from the wells were collected with weighted buckets (50 cm below the water table). Boreholes samples were taken after pumping for 5 min because the average depth of borehole is 100 m (aquifer of fractured sandstones) and the river waters samples were taken in a depth of 30 cm below the surface. The tap and the bucket were cleaned before sampling and caution was taken to avoid splashing. Water samples were collected in 1 L polyethylene bottles. These bottles were previously washed with detergent, rinsed with tap water and then with distilled water and finally rinsed three times with the sampled water from the sources. The water samples were carefully labeled and stored in a cooler at a temperature between 0°C and 4°C. Then they were sent for laboratory tests with the samples sheets containing all the required information, such as the origin and date of collection, the sanitary conditions at the sampling point.

Methods

Laboratory and field analysis for each sample was carried out and nine parameters was measured, three of them are physicals and the six are chemicals. These parameters are: temperatures, electrical conductivity (EC), pH, nitrate (NO3-), nitrite (NO2-), fluoride (F-), chloride (Cl-), ammonium (NH4+) and Zinc (Zn2+). The water sample’s temperatures, pH and EC (physical parameters) were determined from the point of sampling using the portable devices (TABLE 1), whereas the chemical analyzes were performed in the laboratory by referring to the manual of [5] and according to the methods mentioned in the (TABLE 2).

| Parameters | Unit | Materials and Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials | Analytical method | ||

| Temperature | °C | Digital thermometer (portable hand-held DC powered Hanna HI 88129) | Analysis in-situ |

| Electrical conductivity | µs/cm | conductivity meter WTW | |

| pH | pH meter WTW | ||

TABLE 1. Method and techniques used for physical parameters.

| Parameters | Unit | Materials and Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials | Analytical method | ||

| Nitrate | mg/L | Spectrophotometer, model ANACHEH 220 | Sodium salicylate method |

| Nitrite | Method with N-1 naphthylethylenediamine | ||

| Fluoride | Ionometer WTW, model pH/ION 340i and probe F800 | Potentiometric method | |

| Chloride | Spectrophotometer, model ANACHEH 220 | Mohr method | |

| Ammonium | Indophenol blue method | ||

| Zinc | Photometer WTW, model Photoflex Turb Set | Photometric method | |

TABLE 2. Method and techniques used for chemical parameters.

Data processing and statistical analysis

The quality of drinking water and the state of water pollution have been assessed in accordance with WHO standards [6] in order to calculate the number of samples that did not comply with the guideline values.

SPSS software version 21.0 was used for the statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied and the difference between samples was determined by DUNCAN’s multiple comparison test, a safety factor of 95% and a degree of freedom at risk of 5%. The XLSTAT 2015.4.01 software was used for principal component analysis (PCA). The coefficient of correlation between different water quality parameters was calculated by the Pearson correlations test.

Results and Discussion

The results of physico-chemical analysis (mean ± standard deviation, minimum, maximum values) are presented in TABLES 3 and 4. The number of samples analyzed (N) and the WHO Guideline Values (GVs) for drinking water are also indicated.

| Parameter | Sample location | N | Mean ± St. Dev | Min | Max | WHO GV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | Borehole water | 10 | 6.58 ± 0.30a | 6.11 | 7.10 | 6.5-8.5 |

| River water | 10 | 7.17 ± 0.41b | 6.45 | 7.90 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 6.03 ± 0.64c | 5.17 | 6.88 | ||

| Temperature (°C) |

Borehole water | 10 | 31.43 ± 2.95a | 27.9 | 37.0 | 25 |

| River water | 10 | 29.90 ± 2.12ab | 25.3 | 32.5 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 28.24 ± 0.36b | 27.6 | 28.7 | ||

| Conductivity (µs/cm) |

Borehole water | 10 | 288.36 ± 158.50a | 90.7 | 550.5 | 50-1500 |

| River water | 10 | 274.63 ± 132.58a | 100.0 | 500.4 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 617.28 ± 125.52b | 392.0 | 778.0 |

TABLE 3. Variations of the main physical parameters in the samples.

| Parameter | Sample location | N | Mean ± St. Dev | Min | Max | WHO GV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate(NO3-) (mg/L) |

Borehole water | 10 | 41.94 ± 10.75a | 30.36 | 62.48 | 50 |

| River water | 10 | 46.64 ± 9.75a | 36.26 | 65.23 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 32.01 ± 6.75b | 21.20 | 42.48 | ||

| Nitrite(NO2-) (mg/L) |

Borehole water | 10 | 0.97 ± 0.62a | 0.12 | 2.10 | 3 |

| River water | 10 | 1.66 ± 0.55b | 0.84 | 2.54 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 0.53 ± 0.30a | 0.14 | 1.05 | ||

| Fluoride (F-) (mg/L) |

Borehole water | 10 | 0.16 ± 0.16a | 0.01 | 0.52 | 1.5 |

| River water | 10 | 0.49 ± 0.26b | 0.11 | 0.84 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 0.21 ± 0.12a | 0.11 | 0.52 | ||

| chloride(Cl-) (mg/L) |

Borehole water | 10 | 0.67 ± 0.18a | 0.31 | 0.89 | 0.5-2 |

| River water | 10 | 0.69 ± 0.16a | 0.42 | 0.91 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 0.57 ± 0.13a | 0.32 | 0.73 | ||

| ammonium (NH4+) (mg/L) |

Borehole water | 10 | 0.26 ± 0.22a | 0.14 | 0.61 | 0.5 |

| River water | 10 | 0.97 ± 0.19b | 0.69 | 1.25 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 0.25 ± 0.33a | 0.09 | 1.09 | ||

| Zinc (Zn2+) (mg/L) |

Borehole water | 10 | 3.69 ± 0.37a | 2.97 | 4.25 | 3 |

| River water | 10 | 3.05 ± 0.51a | 2.36 | 4.21 | ||

| Well water | 10 | 4.88 ± 1.32b | 2.32 | 7.35 |

TABLE 4. Variations of the main chemical parameters in the samples.

Physical parameters

pH: The acceptable range of pH varies from 6.5 to 8.5 for drinking water. The minimum and maximum pH values (5.17 and 7.90) were observed respectively in the well water and in the river water. The results showed that the average pH values of well, borehole and river are: 6.03 ± 0.64; 6.58 ± 0.30; 7.17±0.41 respectively and they have a significant difference at p< 0.05 (TABLE 3). The well water value is below the WHO range (6.5 to 8.5). This result shows that the pH of these waters has an acidic tendency (pH below 7). The water sources (well) with pH below 6.5 may be allocated to the discharge of acidic products into this source by the agricultural and domestic activities. This is supported by the fact that studies have shown that 98% of all groundwater worldwide is related to the geological nature of the aquifer formations and the lands traversed [7,9]. The pH values for both borehole and river water are within the recommended ranges of WHO drinking water standards. These results are similar with values obtained in borehole waters in Malawi [10-13] as well as those in other countries in Africa [14,15].

Temperature: Water temperature is a physical and ecological factor that has important repercussions on both living and non-living components of environment, thus affecting organisms and the functioning of an ecosystem [16]. The ideal water temperature is between 6°C and 12°C [17]. The temperature of the well water (31.43 ± 2.95) differs significantly from that of the well (28.24 ± 0.36). On the other hand, there is no significant difference between borehole and river water (29.90 ± 2.12) and also between river and well water at p< 0.05 (TABLE 3). The minimum and maximum values (25.3 and 37.0) were observed respectively in the river water and in the borehole water. However, they are all above the WHO standards for drinking water (25°C) (TABLE 3). The high temperatures could be explained by the influence of the ambient heat on the collected water and also by the geothermal gradient of the zone [18]. These results are similar with those obtained in drinking water in the Logone Valley (Chad-Cameroon) [9]. However, high temperature values would not be harmful to human health, but pose a problem of acceptability because fresh water is generally more palatable than warm water [17].

Electrical conductivity: Electrical conductivity measures the capacity of a solution to conduct an electric current. It also makes it possible to estimate the amount of salts dissolved in water [19,20]. The conductivity of a natural water is between 50 and 1500 μS/cm. The value of the electrical conductivity of well water (617.28 ± 125.52 μs/cm) differ significantly from the values of those waters to borehole (288.36 ± 158.50 μS/cm) and rivers (274.63 ± 132.58 μs/cm) (p< 0.05) (TABLE 3). The minimum and maximum EC values (90.7 and 778.0 μS/cm) were observed respectively, in the borehole and well water. Large differences are observed between the conductivity values of well water and those of borehole and river waters. High conductivity indicates high water mineralization [21,22]. The geomorphological context, depth of the levels captured and geological nature of soil formations are all factors that influence variations in conductivity [23]. A study by Sajidu et al. [12] also reported a wide ranging EC values for borehole water supplies in villages of Southern Malawi, namely: Chikhwawa (1450 μS/cm-2800 μS/cm), Nsanje (2150 μS/cm-6600 μS/cm), Mangochi (295 μS/cm-6800 μS/cm), Zomba (129 μS/cm-805 μS/cm) and Machinga (55 μS/cm-1175 μS/cm). Other values (13.90 μS/cm-52.65 μS/cm) have been reported by Ngaram in the Chari River waters in Chad [24].

Chemical parameters

Nitrate ion (NO3-): The presence of nitrates in a water sample may be due to excessive application of inorganic fertilizers, plants and animal decomposition and leaching of wastewater or other organic waste to surface and groundwater [25]. The mean value for well water (32.01 Mg/L ± 6.75 Mg/L) differs significantly (p< 0.05) from borehole (41.94 Mg/L ± 10.75 Mg/L) and rivers (46.64 Mg/L ± 9.75 Mg/L) (TABLE 4). The minimum and maximum nitrates values (21.20 Mg/L and 65.23 Mg/L) were observed respectively in the well water and in the river water. In higher concentrations, nitrate may produce a disease called "blue baby" syndrome (methaemoglobinaemia) which usually affects bottle-fed infants [26]. Despite some sites registering relatively high levels of nitrates, all the mean values sampled water complied with the WHO guidelines limits (< 50 Mg/L). This is in agreement with previous studies in the oil field of Doba-Chad as well as those in other countries in Africa [27-29].

Nitrite ion (NO2-): Nitrites are most of the time absent from surface waters, but their presence is possible in groundwater, mainly because nitrogen will tend to exist in smaller (ammonia) or more oxidized (nitrate) forms. WHO GV retains the value of 3 Mg/L as a quality standard for drinking water. The mean value for river water differs significantly (p< 0.05) from borehole and well (TABLE 4). However, they are all below the WHO GV standards for drinking water, but these sources may not be safe for domestic and livestock use. Lagnika et al. [30] reported averages of 0.072 Mg/L ± 0.14 Mg/L and 5.01 Mg/L ± 1.7 Mg/L, respectively [30,31].

Fluoride: The groundwater is contaminated by fluoride due to geological factors which are the following: the alteration of minerals and the decomposition of certain minerals in earth. The high content of fluoride in groundwater causes severe damage to the teeth and bones of human system result to dental fluorosis and skeletal fluorosis [32]. The concentration of fluoride was found between 0.01 Mg/L and 0.84 Mg/L respectively in borehole and river waters. There is a significant difference (p< 0.05) between the mean value of river waters and those of wells and boreholes (TABLE 4). However, all these values are below the WHO GV standards (1.5 Mg/L) for drinking water. These results revealed a similar pattern with previous studies in the commune of Pobé (Benin) where the mean well water value was 0.142 ± 0.13 [30]. Concentration below 0.7 Mg/L and above 1.5 Mg/L are undesirable. Approximately 1 Mg/L of Fluoride concentration is desirable in drinking waters for public health [33].

Ammonium ion (NH4+): The mean load of contamination of NH4+ in the different sources varies from 0.25 Mg/L ± 0.33 Mg/L in well water, 0.26 Mg/L ± 0.22 Mg/L in borehole waters to 0.97 ± 0.19 Mg/L in the water of the rivers. It appears that there are significantly more concentrations of NH4+ (p< 0.05) in river water samples than in well waters and boreholes (TABLE 4). However, the mean value of river water samples exceeded the admissible level of WHO GV for safety drinking water (0.5 Mg/L). These high values could be explained by anthropogenic activities and fecal pollution originating from animal (spreading of wastewater, livestock breeding, use of animal waste as fertilizer for agricultural land adjacent to water points) and the poor protection of these sources. Lagnika et al. [30] reported averages of 0.193 ± 0.28 and 39.8 ± 13.31, respectively [30,31]. Abdoulaye et al. [34] obtained ammonium ion levels ranging from 0.02 Mg/L to 1.29 Mg/L in November and 0.03 Mg/L to 0.36 Mg/L in July in the water of Senegal River.

Chloride ion (Cl-): The presence of Cl- in the waters is generally due to the nature of lands traversed. They are found in almost all natural waters [17]. WHO GV recommends the range of values from 0.5 Mg/L to 2 Mg/L for free residual chlorine in drinking water. A maximum value of 0.91 Mg/L was measured in the borehole waters, while a minimum value of 0.31 Mg/L was measured in the river waters. The mean values vary from 0.57 Mg/L ± 0.13 Mg/L in well waters, 0.67 Mg/L ± 0.18 Mg/L in borehole waters to 0.69 Mg/L ± 0.16 Mg/L in the water of rivers. There is no significant difference (p< 0.05) between our different values (TABLE 4). They are all within the range of values recommended by WHO GV, which has no impact on the health of consumers.

Zinc ion (Zn2+): Zinc is necessary for humans, but if ingested in large quantities, it can cause an emesis. However, zinc is one of the least toxic metals and deficiency problems are more frequent and more serious than those of toxicity [35]. Of water intended for human consumption, WHO GV recommends as a limit value for zinc 3 Mg/L due to special problems that may cause inconvenience to the consumer (appearance, taste). There is a significant difference (p< 0.05) between the mean value of well waters and those of river and boreholes (TABLE 4). All these values are slightly above the WHO GV, but are not harmful to human health.

PCA profiles of correlation between different parameters

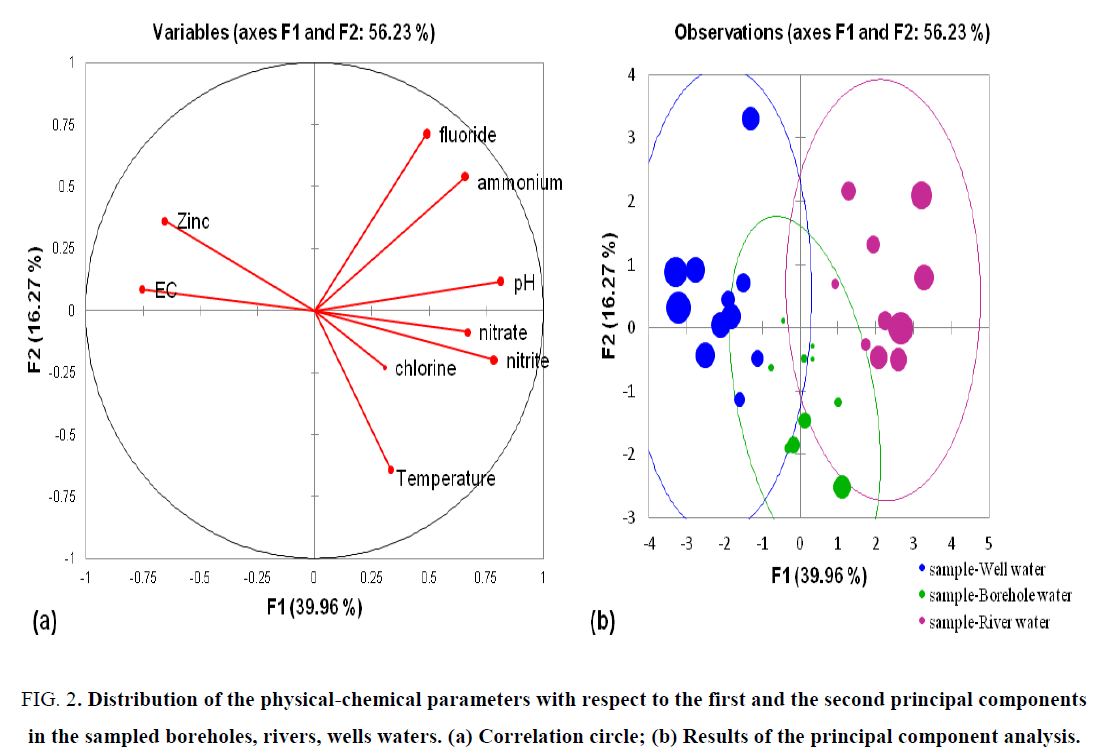

The correlation between physico-chemical parameters was developed using the principal component analysis (PCA). A total of 9 variables were used, namely pH, EC, temperature, NO3--, NO2-, NH4+, Cl-, F- and Zn2+. FIG. 2a shows the correlation circle whose 9 water quality parameters are represented. FIG. 2b shows the results of the PCA performed on the different location of water samples (individuals) from Pelengana commune, compared to the first (F1) and the second (F2) principal components (axes). F1 and F2 principal components respectively accounted 39.96% and 16.27% of the total inertia, corresponding to a total of 56.23%. TABLE 5 represents the value of the correlation between variables and factors (axes) as shown by PCA. Finally, TABLE 6 represents the Pearson correlation between different water quality parameters of the study site.

Figure 2: Distribution of the physical-chemical parameters with respect to the first and the second principal components in the sampled boreholes, rivers, wells waters. (a) Correlation circle; (b) Results of the principal component analysis.

| Axes Parameters | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 0.332 | -0.640 |

| PH | 0.811 | 0.118 |

| EC | -0.757 | 0.086 |

| Nitrate | 0.667 | -0.086 |

| Nitrite | 0.783 | -0.199 |

| Ammonium | 0.657 | 0.541 |

| Chloride | 0.307 | -0.230 |

| Fluoride | 0.490 | 0.713 |

| Zinc | -0.656 | 0.364 |

TABLE 5. Correlation between variables and axes as shown by principal component analysis (PCA).

Based on the PCA analysis, in decreasing order, pH, nitrite and nitrate were highly and positively correlated to F1 whereas EC and zinc were negatively correlated. This axis expresses an acidity and chemical pollution of environmental or anthropogenic origins and is introduced into the sub-soil, either by leaching of fertilizer applied to soil, either by the discharge of wastewater. Compared with axis F2, in decreasing order, fluoride, ammonium and zinc were positively correlated whereas nitrate, nitrite, chlorine and temperature were negatively correlated. This axis expresses a light mineralization. The variance rates expressed are low compared to those of Lagnika et al. [30] and higher than those of Aka et al. [28], which reported 66.8% and 49.25% total variance in the water from wells of the commune of Pobé (Benin) and in the waters of the Alterite aquifers under a wet tropical climate: Case of the Abengourou department (South-East of Cote d'Ivoire) [27,29]. Statistical analysis using Pearson at p?0.05 showed that the parameters were weakly and moderately correlated to each other. A significant positive correlation was found between pH and nitrate (0.455), nitrite (0.558), ammonium (0.605), fluoride (0.401) at p?0.05 (TABLE 6). Similarly, there was significant correlation between EC and zinc (0.484) and a positive correlation between nitrate and nitrite (0.466) at p?0.05. Finally, ammonium and fluoride were significantly correlated at p?0.05 in the collected water samples. It should be noted that there is no significant correlation between temperature and other parameters (TABLE 6). Based on the PCA analysis, three groups could be revealed. Group 1 contains variables (fluoride, ammonium, pH) positively correlated to axis F1 and F2. Group 2 contains variables (nitrate, nitrite, chlorine, temperature) positively correlated to axis F1 and negatively correlated to axis F2. Finally, group 3 contains variables (EC, zinc) negatively correlated to axis F1 and positively correlated to axis F2. In conclusion, the analysis reveals that the mineral composition of the water is almost identical throughout the overall sampling locations.

| Variables | Temperature | PH | EC | Nitrate | Nitrite | Ammonium | Chloride | Fluoride | Zinc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 1.000 | ||||||||

| PH | 0.301 | 1.000 | |||||||

| EC | -0.308 | -0.515 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Nitrate | 0.142 | 0.455* | -0.435 | 1.000 | |||||

| Nitrite | 0.329 | 0.558* | -0.521 | 0.466* | 1.000 | ||||

| Ammonium | 0.020 | 0.605* | -0.412 | 0.227 | 0.480* | 1.000 | |||

| Chloride | -0.041 | 0.240 | -0.060 | 0.215 | 0.154 | -0.061 | 1.000 | ||

| Fluoride | -0.234 | 0.401* | -0.287 | 0.283 | 0.138 | 0.553* | 0.120 | 1.000 | |

| Zinc | -0.225 | -0.319 | 0.484* | -0.406 | -0.510 | -0.180 | -0.438 | -0.167 | 1.000 |

TABLE 6. Pearson correlation between different water quality parameters of the study site.

Conclusions

The physicochemical parameters of different types of water sources (well, borehole and river) used by villagers of Pelengana commune have been measured.

All the analyzed parameters meet the standards set by WHO GV, except zinc ion’s concentration, which is above the WHO GV in all the water sources. The higher amount of ammonium ions was found from the waters of rivers. Regarding to physical parameters, the results for pH, ranging from 6.028 ± 0.64 to 6.58 ± 0.30 for both well waters and borehole waters indicated a measure of acidity, but not harmful to human beings.

In spite of the values of the parameters analyzed that remain within the standards required by WHO, the fact remains that these different water sources considered in this work constitute potential sources of contamination for their status and their methods of operation. Therefore, population using these water sources should be educated about the probably risks when water from these different sources is used for human consumption. Education should also include possible means of treatment of water such as boiling and use of chlorination tablets to avoid potential adverse effects on the health. Moreover, population involvement through protection of drinking water sources from contamination could contribute to improve the water situation throughout the region, thus ensuring a healthy environment. For instance, rules governing activities within the area, particularly pit latrine siting, best management practices for farming, general hygiene and adequate storage practices at household level.

References

- Finance E.T.U.D.E.S, Central B, Recensement DU. 4th General Census of Population and Housing of Mali (RGPH-2009) Analysis of final results Theme 2. 2009.

- PROMISAM Provisional report of the study on the rapid recognition of grain marketing routes and circuits in Mali. 2011.

- AFD Territorial Diagnosis of the Segou Region in Mali. 2016, p:150.

- Owas DE. Drinking water supply and sanitation project in the Gao, Koulikoro and Segou regions. African Fund Dev. 2007;p:54.

- Rodier JB, Legube NM. Analysis of water, natural waters, wastewater, seawater. 9th ed. Paris: Dunod, France; 2009.

- WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO, Switzerland; 2012.

- MM Rev. Geol Dyn Geogr Phys. 1997;21:215-46.

- Seib MD. Assessing Drinking Water Quality at Source and Point-of-Use: A Case Study of Koila Bamana, Mali, West Africa. Environmental Engineering. Michigan Technological University. 2011; p:67.

- Sorlini S, Palazzini D, Sieliechi JM, et al. Assessment of physical-chemical drinking water quality in the Logone Valley (Chad-Cameroon). Sustainability. 2013;5(7):3060-76.

- Chilton PJ, Smith-Carington A. Characteristics of the weathered basement aquifer in Malawi in relation to rural water supplies. Challenges African Hydrology and Water Resources. IAHS Publ. No. 144. 1984.

- McFarlane MJ, Bowden DJ. Mobilization of aluminum in the weathering pro?les of the African surface in Malawi. Earth Surf Process Landforms. 1992;17(8):789-805.

- Sajidu SM, Masamba WRL, Thole B, et al. Groundwater fluoride levels in villages of Southern Malawi and removal studies using bauxite. Int J Phys Sci. 2008;3(1):1-11.

- Grimason AM, Morse TD, Beattie TK, et al. Classi?cation and quality of groundwater supplies in the Lower Shire Valley, Malawi. Part 1: physico-chemical quality of borehole water supplies in Chikhwawa, Malawi. Water SA. 2013;39:4.

- Langenegger O. Ground Water Quality and Handpump Corrosion in Africa. UNDP-World Bank Handpumps Project WSP, World Bank, Washington DC, USA. 1994.

- Bordalo AA, Savva-Bordalo J. The quest for safe drinking water: An example from Guinea-Bissau (West Africa). Water Res. 2007;41(13):2978-86.

- GL. Thermal pollution, influence of temperature on aquatic life. B.T.I. Ministry of Agriculture. 1968, pp: 224-881.

- Degbey C, Makoutode M, Agueh V, et al. French studies and research papers/health-factors associated with well water quality and prevalence of waterborne diseases in the Municipality of Abomey-Calavi (Benin). Health.2011;21(1):47-55.

- Degbey C, Makoutode M, Fayomi B, et al. The quality of drinking water in a professional environment in Godomey in 2009 in Benin West Africa. J Int Santé Trav. 2010;1: 15-22.

- Rodier J. Water analysis: Natural water, wastewater, seawater. Paris: Dunod, France; 1984.

- Pescod MB. Design, operation and maintenance of wastewater stabilization ponds. In: Pescod MB, Arar A, editors. Treatment and use of sewage effluent for irrigation. London: Butterworths, UK; 1985. pp:93-114.

- ML. Ecology of culicid (diptera) and state of malaria in the Tangier peninsula. Ph.D. thesis, Abdelmalek Es Saadi University, Tetouan Faculty of Sciences. 1995.

- Rodier J, Bazin C, Boutin JP, et al. Water analysis: Natural water, wastewater, seawater. 8th ed. Paris: Dunod, France; 1996.

- Hassane AB. Superficial and deep aquifers and urban pollution in Africa: Case of the urban community of Niamey (NIGER), Thesis of Univ. Abdou Moumouni from Niamey (Niger). 2010, p:198.

- Ngaram N. Contribution to the analytical study of heavy metal pollutants in the waters of the Chari River during its crossing of the city of N'djamena. Doctoral Thesis Ph.D. 2011. p:164.

- Ademoroti CM. Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology. Ibadan: Foludex Press Ltd., Nigeria; 1995.

- Karu E, Ziyok I, Amanki ED. Physicochemical analysis of ground water of selected areas of Dass and Ganjuwa local Government areas, Bauchi State, Nigeria. Sci Educ Publ. 2013;1(4):73-79.

- Maoudombaye T, Ndoutamia G, Seid Ali M, et al. Comparative study of the physico-chemical quality of well waters, drilling and consumed rivers in the Doba Petrolier Basin in Chad. Larhyss J. 2015;24:193-208.

- Aka N, Bamba S, Soro G, et al. Hydrochemical and microbiological study of Altérites aquifers in humid tropical climate: Case of the Department of Abengourou (South-East of Côte d'Ivoire). Larhyss J. 2013;16:31-52.

- Sajidu SM, Makhumula P, Masamba WRL, et al. Fluoride Content and Chemical Water Quality in Borehole Water in Selected Rural Areas of Southern Malawi. Unpublished Paper. 2004.

- Lagnika M, Moudachirou I, Jean-Pierre C, et al. Physico-chemical characteristics of well water in the municipality of Pobé (Benin, West Africa). J App Biosci. 2014;79:6887-97.

- Saizonou M, Yehouenou B, Bankolé HS. Impacts of slaughterhouse waste in the degradation of the water quality of the water table. 2010. p:79-91.

- Udhayakumar R, Manivannan P, Raghu K, et al. Assessment of physico-chemical characteristics of water in Tamilnadu. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;134:474-7.

- Subba Rao N, John Nevada D. Fluoride occurrence in ground water in an area of peninsular. Environ Geo. 2003;45:243-51.

- Abdoulaye D, Salem KMM, Kankou OAO. Contribution to the study of the physico-chemical quality of the water of the right bank of the Senegal River. Larhyss J. 2013;12:71-83.

- Araujo RN. Assessment of the Current Contamination of Heavy Metals and Certain Persistent Organic Compounds in Fish of Sport Interest from the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City. Essay presented at the University Center for Environmental Training. 2013, p:83.